Publication by Leon Barkho, professor at the University of Sharjah

Léon Barho, Professor at the University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, former Reuters correspondent and AP staff columnist, has become an academic after retiring from international news reporting.

Leon sent in his publication for the Calligraphy Museum, which we want to share with you.

"Archaeology, culture and art have always fascinated me as a journalist and I have written extensively about them; I find this piece about the first letter of the Arabic alphabet, Alif, which is considered sacred by Arabs and Muslims, very interesting.

At first glance it appears to be the first letter of the Arabic alphabet with a numerical value equal to the number 1.

But the letter presents different concepts. The letter stands for God, the one, the first, the beginning and the last.

It is the letter Alif of the Arabic alphabet that captivated artist Nada Abdallah. She has dedicated her energy, time, skill and knowledge in Arabic calligraphy to this alphabet.

Ms. Abdalla openly states her commitment to the script. "Alif is the beginning, the first letter of the Arabic alphabet and the first letter of the name Allah," she says.

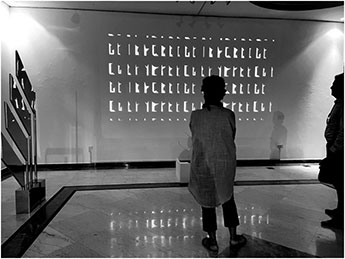

"Back to Alif" was the title of a solo exhibition at the Rawak Gallery, College of Fine Arts and Design, Sharjah University, as part of the Sharjah Biennial of Calligraphy celebrations.

She has chosen to portray the beauty of Arabic calligraphy and to showcase its history, styles and forms.

Her calligraphy comes in different forms and can be seen in posters, sculptures, murals and animations.

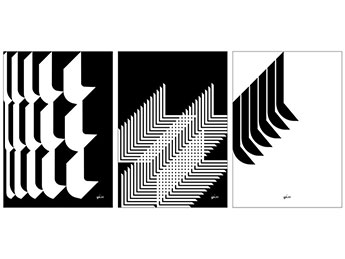

"The transformation in styles of Arabic lettering could be seen in Alif of every lettering," said Ms. Abdalla. - With different sizes and vertical alignment of the lettering, the nature of the style can be determined. The alif acts as a symbol for the lettering, through which experts can identify the style and type of lettering. Ms Abdalla's work aims at identifying the Kufic Alif and showcasing the possibility of creating new styles using the latest media, digital design and technology.

"Each line of Alif begins with a sequence of dots and moves up or down to form a vertical line of the sacred letter ... In turn, the letter is transformed into different forms depending on the script used," she adds.

In the earliest manuscripts, the basic Kufic Alif was short and bold, "reflecting the emphasis on the religious content rather than the visual," she says.

In her work, Ms Abdallah has turned her fascination and devotion to Alif into elegant raised vertical strokes.

She continues, "Alif's journey from East to West and from past to present highlights levels of development."

Kufic, the calligraphic script to which Ms. Abdallah is so attached, is Arabic script, which was invented in the seventh century in the southern Iraqi city of Kufa. The script reached its peak in the 9th century, illuminating Qur'anic manuscripts, parchments, inscriptions on tombstones, architectural decorations, bows and coins. Kufic handwriting comes in different types and characteristics, as do the varied styles of Mrs Abdallah's Alif.

Some of the most notable types of Kufic are Fatimid, Qayrawani and Mamluk, each denoting a Muslim dynasty or geographical area of the Muslim world. The kufi is known for its decorative style and motifs with leaves, knots, jagged, squared and other types combined with characteristics that can be unique, angular, straight, horizontal and playful.

A traveller to an Arab or Muslim country may see Kufic script almost everywhere, probably without giving it much thought.

Kufic can be on logos, billboards, signs, newspapers and magazines, above all as part of architectural marvels in which verses from the Muslim holy book are carved into the niches and walls of mosques.

Ms. Abdallah's Kufic letters contain mainly traditional elements and themes that have become part of people's lives in the Arab and Muslim world.

Ms. Abdallah's calligraphic works make extensive use of religious symbols. Muslims hold Alif sacred, hence her interest in the letter which signifies the Almighty.

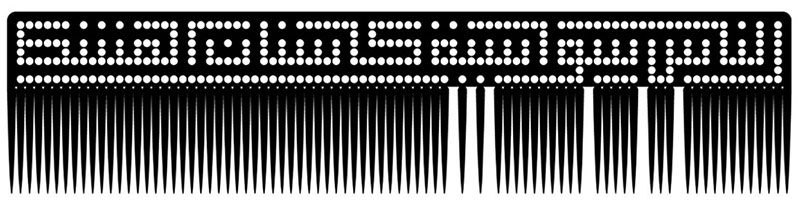

Another of her prominent calligraphies is based on a saying of the Muslim Prophet Mohammed. The work, titled "Sawasya" or "Equality", visualises the concept behind the Prophet's statement that "human beings are equal as the cogs of a comb", irrespective of their colour, religion, orientation or race.

"In this context, the comb means unity and non-discrimination," she says.

Like her Alif, Ms Abdallah's Savasya typography is based on ancient Kufic calligraphy "to connect with the religious aspect of the content".

"The text is presented in a point Kufic style designed specifically for this project," she says.

Ms Abdalla uses multiple dots to draw attention and "create visual lines and solid figures worthy of more attention".

She produced and exhibited her 'Savasia' at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic to emphasise "the importance of unity, collaboration and interconnectedness". An artist, designer and educator, Ms Abdalla is the founder and director of the Bilarabic Design Festival, an event aimed at promoting Arab culture and design as a dynamic platform for open collaboration.

She has exhibited her work in Lebanon, UAE, Greece, Korea, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, USA and numerous other countries. Her interest in Arabic calligraphy, work and research in this field dates back to the 1990s.

She studied at the Sharjah University College of Fine Arts and Design for many years; Ms. Abdalla and her students created Arabic scripts inspired by Arabic calligraphy, developed a Latin script inspired from Arabic letters and devised new methods of working with the Square Kufic script. Her students developed Arabic typography based on the typeface they created for the UAE national anthem, in the shape of the UAE flag.

This gorgeous design was transformed into a mural which now adorns the entrance to her college and has been exhibited at ATypI, the Paris Typographical Association.

The association organises conferences on everything imaginable relating to type design and typography'.

Back to Alif, Logo Design, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.

Back to Alif, Logo Design, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah. Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.

Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.  Alifs, Same but not Similar, Stainless Steel Mirror, 238 cm x 118 cm, Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.

Alifs, Same but not Similar, Stainless Steel Mirror, 238 cm x 118 cm, Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.  Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.

Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.  From Left to Right.

From Left to Right.Transformed Alif, 2022, Ultraviolet Printing on Uncoated Paper, 70 cm x 100 cm

Mihrab Alif, 2022, Ultraviolet Printing on Uncoated Paper, 70 cm x 100 cm

Qairawani Alif, 2022, Ultraviolet Printing on Uncoated Paper, 70 cm x 100 cm

Back to Alif, Sharjah Calligraphy Biennial 2022, College of Fine Arts and Design, University of Sharjah.

Sawasiya, Aluminum 200x460 cm, exhibited in Abu Dhabi Art 2020.

Sawasiya, Aluminum 200x460 cm, exhibited in Abu Dhabi Art 2020.Calligraphy — the written beauty of feelings.