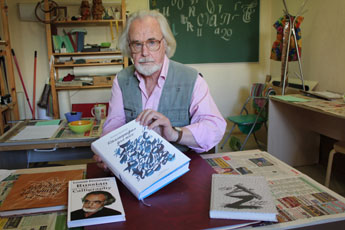

Interview with Leonid Pronenko

A cozy little studio in Krasnodar is home to the “Master from A to Z” calligraphy school. The Calligrapher magazine visited Leonid Pronenko, Professor and the Honoured Artist of Russia, who teaches at the school, for an interview. The master spoke about his journey into the world of calligraphy, shared some secrets of the profession, and his vision of art today.

– Please tell us about yourself. Why have you chosen the artistic path?

– My original speciality was turbine operator; I worked in the field for some time before I was recruited to the army. In the last year of service I met a Kazakh who had studied in an art school. In his spare time he did sketches, and I got interested, too, so I started drawing myself.

I was lucky: a local artist and collector Alexander Chaplygin noticed me and suggested to enroll to the Voronezh University of Civil Engineering. Surprisingly, I managed to enter, though it entailed certain escapades. But soon I realized that what I really wanted to study was painting. Then Alexander introduced me to a well-known Voronezh artist, and the latter reprimanded me: "Mr. Chaplygin was very kind to take you, and you ought to appreciate what you are offered. You know nothing about the colour or the composition anyway,” he went on.

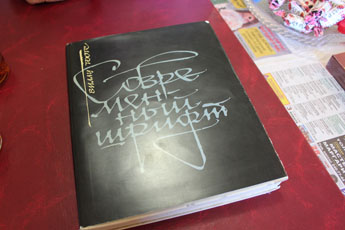

But I did not give up. I returned home, and my mother introduced me to a painting teacher she knew. He taught me for a year, after which I managed to enter the arts faculty of the Kuban State University, although I was already 27 by then. I made good progress, learned to feel the colour and everything. When I graduated from the University, they offered me to study further. I thought I wanted to do painting, but then I laid my hands on a book by Villu Toots, and I fell in love with calligraphy. I realized that there was nothing more beautiful in the world than the script.

I wangled myself a place to study in Tallinn, despite the fact that they only accepted Balts. When I got there, the head of the department asked me about Krasnodon. I had to clarify that I was from Krasnodar, not Krasnodon, which disappointed him.

I had three internships in Tallinn, three month long each, during which I was lucky enough to get to know Villu Toots. We even became good friends and communicated ever since.

Then I won a contest and a 10-day trip to the USA, where they offered me to stay on for three months. It was not as easy as it sounds, of course: the university wouldn’t let me go as they were afraid they would have to pay for my stay in the U.S. I spent several days waiting for my travel allowance only to discover I should have been waiting somewhere else. Fortunately, I managed to get the money the very last moment. A fun fact: when I was already in the plane, they announced there was a Russian calligrapher aboard and offered me vodka. While in the United States, I visited San Francisco, New York, San Diego and other cities, met with local artists, and attended workshops, showing what we had, too.

What more can I ask for? I’ve had quite some exhibitions over the years. We’ve recently had an inventory count at the university, and my publications took up a whole room.

– What is calligraphy for you?

– It is everything: the lifestyle, the paper, the tools, the faculty, etc. Everything...

– It is interesting that you call calligraphy a lifestyle. What kind of person should a calligrapher be, in your opinion? Can anyone do calligraphy, or should he or she have a certain predisposition?

– Anyone can become one, as long as they love it. For example, some Friedrich Poppl spent three years after the Great Patriotic War in Soviet captivity, and then he returned home and spoke well of the USSR, and became a distinguished calligrapher. How? Why?...

Another story: there was an American, Ward Dunham, who had never even thought about calligraphy. During the Vietnam war, he was a martial arts instructor: a tall, broad-shouldered, manly. Once he saw a captive Vietnamese sharpen a match and write with it. He was intrigued and asked the Vietnamese to teach him. And then he became a renowned calligrapher.

Calligraphy is something that should touch your soul.

– What impact does calligraphy have on your personality, do you think?

– Many scientists who study the human brain note that calligraphy is good for developing fine motor skills, especially for children. When practicing calligraphy, your mind relaxes. I can corroborate that.

– In work, do you believe in inspiration or prefer to stick to a schedule?

– People are different. Some believe that the right thing is to sit down to work in the morning, and inspiration will come in the process. For others, the only option is to create is in the flurry of inspiration. I’m somewhere in between.

With Villu Toots, for example, it was like that: sometimes I visited him, and he would lay the table, have a drink and not write a single word that day; on the other days though, he would work around the clock.

– Whom can you call your teacher, except Villu Toots?

– Many artists influenced me. But mainly it was Villu Toots. I spent a total of 9 months in Tallinn, attending his exhibitions, making speeches. He was my ideal.

– How would you describe your style?

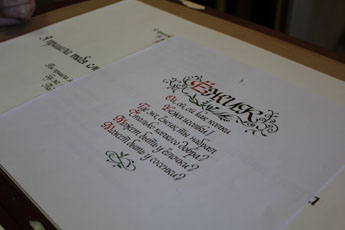

– Calligraphy has evolved as a result of work of numerous scribes. Someone would note something and make it a rule for himself. Likewise, everyone gradually develops their own tricks. Even if we take the basic cursive writing, every master adds something of his own to it. I am no exception.

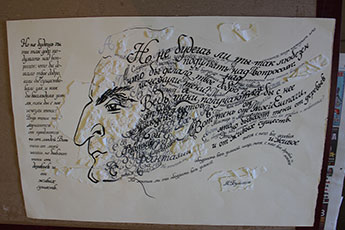

Nowadays it’s all about fancy nibs and expensive paper. Back in the days, Hermann Zapf used to write on the back of wallpaper and never minded any kind of paper, because for him new materials meant finding new ideas, new approaches, dealing with new challenges. You don’t really need expensive materials to create a masterpiece. All you need is a handmade quill, which you can sharpen and shape to your liking: make it straight, or leftside, or double-split – whichever comes to your mind.

Ink or any dye, and a simple sheet of paper. That’s all you need, really. Some of my works created like this have been purchased by international museums. Here’s an anecdote. I was staying with a calligrapher once. I created a piece, but didn't like it, so I crumpled it and threw it away. The next day a housemaid came to clean the room, and in the process she found the crumpled sheet. And just as she was unfolding the paper, the master entered the room. He saw the piece and asked me to sell it!

– Do you have a favourite script, the one you especially enjoy working with?

– Something similar to the Italic. Nobody wrote like that before Villu Toots: simple, but elegant, creatively different. He found his own approach, and many imitate him these days.

When in San Diego, I participated in selecting the works for a book to be published. I saw a couple of pieces by one artist and really admired them. But then I looked through his other works, and they were all alike, with one and the same composition. I didn’t vote for him in the end. A calligraphy artist must come up with a new approach, a new composition. There is no point in writing one and the same thing over and over.

– Do you have a favourite letter?

– They all are beautiful, I love them all.

– You have several works with quotes from Edgar Allan Poe. Do you prefer to write your own text or borrow a quote from the literature classics?

– I really love Poe, I made 10 or so works with his quotes. I sold many of them in the USA. I like his Russian translations, every one of them is unique in its own way.

– Do you have a favourite artwork of your own?

– There are those I like more than others. For example, “A Conversation with Calligraphy”, or some simple works made in a single burst of creativity that came out perfectly composed.

– What project are you currently working on?

– Recently I have been working on a book, which is a joint project with one of my school’s first students, Pavel Babenko. He writes poems, comparing himself with Omar Khayyam. I arranged his poems and made the titles. I only finished it a short while ago.

– You once promised in an interview to create a moveable type. Have you had a chance to start implementing the idea?

– Unfortunately, no.

– What is the best way to start learning calligraphy?

– In “Master from A to Z”, we start with learning to write the basic elements. I believe that it is appropriate to add expression only after having studied the classics. It is essential to master the basics, the classical proportions, to be able to understand nuances and deviations. We all start with the classic Italian cursive. It encompasses all the intricacies of mastering the dip pen. Once you have grasped the Italic, it is much easier to learn any other script.

Why do I evangelize the broad pen? Because with the pointed pen, it is easy to sign a postcard or similar. But what would you do with large spaces? A wall, for example? I once saw an American writing on a wall with an oblique cut broom and paint. How would you do something like that with a small instrument? It offers no space for creativity.

The beauty of the letter emerges when there are beautiful start and end elements, when elements blend one into another, like drops of mercury. And this requires precision. In painting you have the option of correcting a mistake with the palette knife, while in calligraphy you have no margin for error, otherwise you will have to rewrite the entire piece. This creates the habit of discipline. You learn to draw a line while seeing the whole picture at the same time. Otherwise it would be like teaching a child to ride a bicycle while only looking at its wheel. When drawing a line, you need to see the end point.

– What is the first thing to learn in calligraphy?

– The anatomy of the letter. Unfortunately, there is not enough literature about this, and most of it is not available in Russian. There have been some great self-learners, but they trained few great masters.

– And how did you start teaching and came to lead the “From A to Z” school?

– I was growing dissatisfied with the way I had to work in the university. In the beginning, we had plenty of calligraphy classes. Students practiced calligraphy drills from the first till the 7th semester covering huge sheets of paper with letters. And then they began closing down disciplines one after another: oil painting, drawing, and finally, calligraphy. I wanted to teach calligraphy to those who were really interested. I want to train like-minded people, people who would work in the field.

– How is your school different from others?

– We work with broad nib only. Some offer online classes, but I prefer live communication. I spend three hours a day walking constantly among my students, correcting their mistakes, explaining the anatomy of every character, or writing on the blackboard. And I am not doing it for the money.

I am constantly trying to impress it on my students that quantity does not mean quality. How can it become quality if you systematically make one and the same mistake until it becomes automatic? You need a teacher to be near to correct you; otherwise the mistake will implant itself in your muscle memory. For quantity to turn into quality you have to write but also compare and analyze how what you do is different from what your teacher does.

Among my students there are not only people from the arts sphere. There are also psychiatrists, for example. Everything depends on your willingness and readiness to progress.

– Which of your students can you distinguish among others?

– Alexander Yakovlev, for example. He knew nothing about calligraphy when he started, but he worked hard and made great progress.

– How did you decide to write your first book?

– I always had a fine skill of writing. As far back as in school my teacher used to say to me, despite my poor marks in her class, that I was going to be a writer. What sort of writer could I become if I always scored Cs?! But she turned out to be right after all!

When I met Villu Toots, he treated me very well. He offered me to write articles about calligraphy, and they turned out quite good. I wrote materials for the Young Artist, In the World of Books and some other magazines. Once I received a letter from someone saying they got interested in calligraphy after having read my articles.

I saw then that texts about calligraphy could be interesting, and I decided to write a book, which would be simple and entertaining. Konstantin Burov (a Soviet book artist) supported me and helped with publishing it.

“Calligraphy for Everyone” is the first book in Russia devoted entirely to the art of fine writing. Villu Toots has a very popular book, but it also deals with lettering and typographic fonts, while mine only focuses on calligraphy. In Soviet times, it was difficult to get books from abroad, it was impossible to communicate. My books got returned, as you had to get a permission from the Ministry of Culture first to send the books out. So many of the artists who participated in the creation of my book never got their copies. The first edition of the book was just lying around for a year and a half, because nobody knew whether it would be interesting. And now a new edition is on the way: things are moving forward, calligraphy is becoming popular.

– Why do you think your book was successful?

– Because we don’t have enough Russian books about calligraphy, most of the books are translations. It was the first original Russian edition. The third edition will be extended, better paper, high-quality and colour illustrations. There will also be some rare artworks and letters from calligraphers added from my archives. General interest towards calligraphy is now growing.

– And how did you come up with the idea of your second book, “Russian Calligraphy. One Teacher, 222 Students”?

– It’s that so many interesting things had happened over the years of me teaching calligraphy. I remembered some of them and recorded the others. I had also gathered many interesting works created by the students during classes. And they got published. It is the first book in the world containing over 200 works made by students studying under one teacher. I have expanded it since, changing the works with new ones, arranging them differently, with only the stories remaining the same.

– How can one learn to perceive and understand calligraphy? What should one look at in the first place?

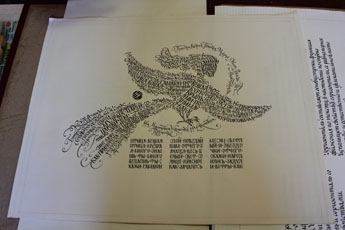

– Firstly, the anatomy. Secondly, author’s individual approach. It's one thing to copy a script, and quite another to bring something of your own into it. Thirdly, of course, the composition. I know many artists who can paint perfectly, but when it comes to the compositions they get lost, turning out to be just the performer, but not the creator.

– What is the way to interpret abstract calligraphy?

– Abstract calligraphy requires an unusual composition: the theme or the subject can be presented in an abstract way, but stressed with the colour or the composition. Usually those who practice abstract calligraphy can boast an excellent classical education. You can see the movement of the hand, the brush, the colour behind the abstraction. You can always distinguish a poor solution from a competent one.

– Do you think calligraphy should be a separate art form?

– Yes, I do. It is very different from oil painting or graphics. They can always be combined, of course. There are works, which sit at the intersection of graphics and calligraphy.

– Do you see any new trends in contemporary calligraphy?

– Everything old is new again. I do not think we will discover anything new now. Our calligraphy has been forgotten for so many years that it is hard to predict anything. Even the major figures in the arts were not familiar with calligraphy, while our ancestors have been embellishing their calligraphy skills for centuries. The 16th-17th centuries saw calligraphy blossoming; now it repeats itself again.

– How do you see the future of calligraphy in, say, five years from now?

– I would love to see calligraphy given more use. Villu Toots decorated more than 500 books with handwritten scripts; we do not have such practice as yet. Calligraphy should have the same rights as painting, sculpture, etc. And I believe the times will come soon, since there is a growing interest towards it. There are exhibitions arranged, handwritten books published. For example, a shortened handwritten version of Don Quixote made by Ilya Bogdesko has been published.

Calligraphy can be applied to sculpture, metal, etc. The point is that a text is based on a handwritten script, and whether it is embossed in stone or written on a sheet of paper is secondary.

The International Exhibition of Calligraphy in Moscow helps greatly to promote the art. I once suggested having a calligraphy exhibition and organizing a museum here, in Krasnodar.

However, the idea received no support here. And Alexey Shaburov, having once read my article about calligraphy, offered assistance for the development of calligraphy. He created a unique project – the International Exhibition of Calligraphy, which was attended by invited guests from the U.S., France, the Netherlands, Germany and many other countries. But it was also important to create a place to collect under one roof examples of contemporary calligraphy, so that people could see not ancient manuscripts, but the modern interpretation of the art. I am happy that there is now such a wonderful museum. (note: the Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy)

– Finally, what advice can you give to those starting on their way in the world of calligraphy?

– Find a good teacher, a real calligrapher, and unleash your creativity!

For the largest part ill handwriting in the world is caused by hurry.

(Lewis Carroll)