The Most ‘Chinese’ Chinese Character

‘He’ — the most «Chinese» character

‘He’ — the most «Chinese» character

If, as Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, you can infer a nation’s spirit from its language, then what to make of modern Chinese?

In a revealing exercise, China Heritage — a National Geographic-like monthly with a glossy interest in the roots of Chineseness — recently organized an effort to identify the 100 Chinese characters that «carry the most meaning for Chinese culture.»

The results are fascinating, alternately rife with political irony and revealing of a Chinese reality not always apparent to outsiders.

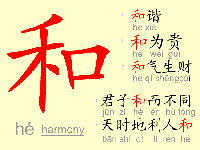

Culled from an initial pool of 374 characters suggested by an unidentified committee of historians and linguists, the most Chinese of Chinese ideograms was identified as 和 (pronounced ‘huh’ and typically Romanized as ‘he’) — the character for an indistinct concept often (though clumsily) translated as «peace» or «togetherness.»

The selection won’t come as a surprise to China watchers. He is the first character in both «harmonious society» (和谐社会; hexie shehui) and «peaceful rise» (和平崛起; heping jueqi) — terms the Chinese Communist Party has recently coined to explain its domestic and foreign policies, respectively, and which are therefore printed ad nauseam in newspapers and on propaganda banners throughout the country.

The character has deeper roots in the Chinese psyche than that contemporary sloganeering, however. It has been a favorite of Chinese philosophers — including that icon of Chineseness, Confucius — for at least a couple of millennia. It also appears in «fairness,» «balance,» «warmth» and a host of other terms that reflect the long-held aspirations, if not the lived reality, of many a Chinese person.

The irony? The most Chinese of Chinese characters is also one of the most sensitive on Beijing’s list of banned words, thanks to the Nobel committee’s naming on Oct. 8 of dissident Liu Xiaobo as winner of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize (和平奖; hepingjiang).

The rest of the list contains many of the usual suspects — the characters for «dragon,» «jade,» and «ritual» all made the cut. Others, such as tan, the character for «corrupt» or «greedy,» are more surprising, if no less appropriate.

«Tan / corruption is like a film of rust on the surface of Chinese culture,» Li Ming, a member of the Shandong Province legislature and a participant in compiling the list, told Xinhua. «It’s been there with Chinese people for thousands of years.»

The list also offers a compelling take on China’s economic development. While some entries such as gong, meaning «labor» or «industry,» are suggestive of China’s record-breaking modernization drive, they are far outnumbered by characters — field, plow, farmer, family, grain — linked to the country’s agrarian roots. In other words, the China of gleaming skyscrapers and luxury sedans experienced by visitors to cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, and promoted by Chinese officials and business consulting firms, has yet to replace the China of packed-earth courtyards and ox-drawn plows, at least in the minds of Chinese people themselves. The question, with tens of millions of Chinese migrating from the farm to the city, is what sort of national spirit future lists like this might reflect: A rural yearning for warmth and balance, or a cosmopolitan thirst for personal wealth and individual freedom?

Source: The Wall Street Journal

When there are no words left, the meaning is still preserved.