Power and mastery of the blank space — Toko Shinoda

When speaking of Japanese art, people use words such as wabi and sabi, words that speak of a delicate sensibility and an ephemeral existence. Viewing the retrospective currently being hosted at the Musee Tomo in Tokyo’s central Toranomon district in celebration of the 100th birthday of Toko Shinoda, the first word that comes to mind is «power.»

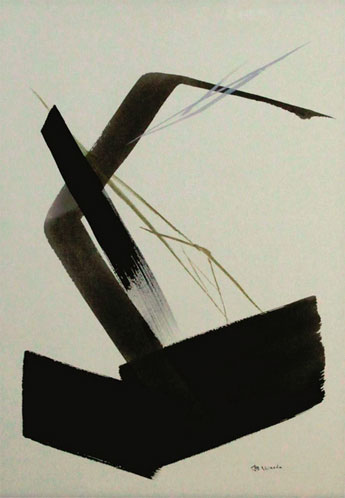

The power is observed in the elements that constitute Shinoda’s paintings — the strength of her calligraphy-style strokes, the stark intersections of lines and planes and the evocative contrasts she creates in her ink between shades of black and gray.

Although the market for Shinoda’s work transcends her own culture — owned and appreciated as it is internationally — it carries with it the strength of a tradition that defines the Far East. Looking at her paintings, one can almost catch a glimpse of the artist centering her mind as she rubs the ink stick on the ink stone, and experience the tension as she first envisions on the blank surface the design she has created in her mind, and finally commits it to paper. Calligraphy is an art that is unforgiving of ill-made strokes. So too is Abstract Expressionism, the international art movement that influenced Shinoda’s work. Her strokes are well and carefully thought out, but executed with a determination, suppleness and immediacy.

Shinoda was born in Dalian, Manchuria, on March 28, 1913, but her family returned to Tokyo soon after. Her great-uncle, an official seal-carver for the Meiji Emperor and therefore a master of both calligraphy and sculpting, passed his interests in calligraphy and Chinese poetry to Shinoda’s father, who passed them on to her. Shinoda was also inspired by the aesthetics of the playwright and actor Zeami (1363-1443), whose ideas about theater and performance had a major effect on Japanese art and literature. This influence is reflected in her fondness for waka poetry written in the cursive hiragana alphabet, rather than the heavier style of Chinese calligraphy.

Shinoda’s early years were devoted primarily to calligraphy, and a review of documents from the exhibitions she held in the mid-1940s reveals an interest in the abstraction of calligraphy. In the early 1950s, Shinoda’s works were selected for two exhibitions of calligraphy mounted by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which toured North and South America. Soon she was commissioned to create murals for the Japanese Pavilion at international trade and culture expositions in the United States, Brazil and Sweden. By the time she arrived in New York in 1956, she was already known in art circles.

Shinoda spent a decade going between New York and Tokyo, just when Abstract Expressionism was at its zenith. The spontaneity of her calligraphy and her desire to adapt it to new ways of expression matched the New York atmosphere perfectly. As she is fond of saying of her New York contemporaries, «they had Abstract Expressionism, but I had calligraphy, too.» Shinoda had several solo shows in the U.S. and Europe and her works were exhibited and sold at the gallery of Betty Parsons, the doyenne of Abstract Expressionist gallerists, who handled, among others, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Jasper Johns.

In practicing her art, Shinoda wields the concept of yohaku (empty space) with incredible precision. Not only does she place design elements elegantly in two dimensions, but she has also developed this sense in three dimensions, as is witnessed by numerous works executed as architectural elements. The mural in the Kyoto International Conference Center (1962) and several murals made especially for the main hall of Zojoji Temple in Tokyo’s Shiba district (1974) are wonderful examples. The current retrospective, which was curated by gallerist and long-time Shinoda supporter, Norman Tolman, is being held in a museum that incorporates into it two calligraphic paintings that demonstrates the artist’s sense of yohaku in three dimensions: «Portrait of a Woman,» which pulls visitors through the entry lobby, and a wall mural of the «Iroha» poem that draws them down the stairway into the exhibition area.

Although Shinoda has used many of the same elements in her paintings and prints over the years, her creativity in placing them in dramatic positions and juxtapositions has never lagged, nor has the energy and power with which she paints. «Memory,» a 1996 work that appears in the exhibition, has all the artist’s characteristic elements and has all the power — but in a more controlled manner — of «Discovery,» a 1962 work also featured in the retrospective. Asked whether she continues to paint on a daily basis, the centenarian responded that she paints when the mood strikes. But, it seems the mood and the muse never stray too far. A recent work included in the retrospective features the character for fire and it seems a clear indication that the fire to create still burns brightly inside.

Source: japantimes.co.jp

Calligraphy is frozen poetry.