Interview with Vladimir Popov

The Calligrapher magazine met with an outstanding Russian Islamic calligrapher Vladimir Popov for an interview in his cozy workshop apartment.

– You are a living legend. Tell us about yourself.

– I was born in 1924, served as an artillery scout during World War II, participated in the capture of Berlin. I have 15 awards: two Orders of the Patriotic War, 2nd class, the Medal for Battle Merit, the Order of the Red Star, etc.

After the war I studied at the Kazan Art School, participated in national, republican and all-Union exhibitions. But when I struck seventy, my life changed: I discovered the world of calligraphy.

Here’s a good story for you. Some time in the 1990s I was in Moscow and, being an aspiring calligrapher, decided to go to the State Museum of Oriental Art to study tughras as made by established masters. And you wouldn’t believe it: I went around the whole exhibition and didn’t find any. It turned out, the whole oriental world had forgotten about this form of calligraphy. And I'm trying to bring it back.

Najip Naqqash was the first to revive the tradition of tughras here in Tatarstan. He works with the traditional form, as did masters centuries before. I even took lessons from him.

In 2000, I was very lucky to have two personal exhibitions in Moscow: one in the State Museum of Oriental Art (curated by Tatiana Metaxa) and the other in the Egyptian Cultural Centre (curated by J. Marcus.) They usually book museum halls for exhibitions for no more than 13 days, but my pieces stayed there for 44 days, with a flow of visitors never ending. And then in December of the same year the Government of Tehran invited me to take part in the 8th International Festival of the Koran and Calligraphy. There were representatives from 17 countries, and over a thousand local participants.

I was immensely happy that, being a calligraphy beginner, I was invited to a festival of such scale. Before that, I had not known for sure what I was doing. And it was there when I realized it: the way was to do what you believe is right, not looking at others. Surprisingly, I was awarded second place in the contest, while a calligrapher from Malaysia took the first. He left me an inscription that said “It is wonderful to meet a brother, an adept of the same religion, who respects it while developing the art further.” And so, as of 2000, I started to feel more confident and allow creative experiments into my work. Cultural exchange is crucial for creativity: it is wrong to live in your frozen quagmire; you need to go and see the world in its diversity.

Further on, I exhibited copies of my works in the lobby of the Russian Council of Muftis, participated in the second With Faith, Hope, and Love interconfessional exhibition. All my artworks are permeated with a call for peace, love and harmony. It is crucial for me to show the importance of these notions, to bring them to people.

In 2003 I was awarded the title of the People’s Artist and Honoured Artist of Tatarstan and the Russian Federation. Three years later, I had a series of exhibitions in the major cities of Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon. I was planning to take my exhibition further to China, Laos, South and North Korea, Mongolia, and then back to Russia, but unfortunately I had to call it off due to health problems. But now I am full of vim and vigour, and ready to create.

I feel deeply honoured to have my works in the Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow, in the Russian Centre of Science and Culture in Cairo, in the Bolgar Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve, in numerous museums of Tatarstan, and even in the collection of Iran’s former president Mohammad Khatami.

– Why did calligraphy attract you in the first place?

– I don’t really know why I started. By my 70, I had tried everything: oil painting, tempera, watercolours. I painted portraits, landscapes, tried easel painting of all kinds, etching, xylography, and so on. I tried every form of art except for sculpture. But it was calligraphy that touched something in my soul.

The Arabic alphabet is unique. Take, for example, the German alphabet: it’s either the classic or the Gothic writing. While in Arabic there are more than 20 scripts: Kufi, Sulus, Naskh, and many more. Every letter is drawn differently depending on its position in the word: it’s a sophisticated art.

Arabic writing is based on tradition. Boys are taught writing when they turn five, with strict teachers applying to corporal punishment to make the pupils adhere to the traditional rules, making their writing almost robotic. A calligrapher in the Muslim culture must strictly follow the canon.

I believe that the artist is ought to experiment. What is Allah? I think it is an abstract notion. Artists have been recreating the emblems of Allah and Mohammed for one and a half thousand years without changing. And I have written them in a variety of styles. I have nothing to do with the Sharia law, so they cannot punish me: I am an artist and my own master, and my art is my vision.

At an international book fair in Moscow, my manager once saw an album with Islamic calligraphy. When he told me that the album included Mohammed’s name written in an unusual manner, I was surprised and asked him to get me that book – only to discover that it was a work of mine in it!

I have nothing to do with religion, and yet I’ve ben officially recognized as a brother to Islam. It was in 2000, the year I met Rashid Bat, that he, together with a Tunisian sheikh signed such a document. There was an exhibition this September, and Bat and I met again 18 years after that. Actually, it’s a rather tangled tale.

My student Gulnaz Ismagilova had participated in an exhibition in Algeria, and Rashid Bat, who was also there, had noted her and gave her calligraphy classes throughout all the 10 days of the exhibition. They exchanged contacts. I visited her after she had returned, and on her photos from Algeria I saw a familiar face – the very Bat from Pakistan! She wrote to him about it, and the calligrapher marveled over the fact how, among all the exhibition participants, he marked out none other than my student. Bat and I kept in touch since then. And in September a number of foreign calligraphers were invited to the Kul Sharif Mosque, with representatives from Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, and of course, Rashid was invited, too. Thus we met again after so many years!

– What is calligraphy for you?

– I can only interpret Islamic calligraphy. I have only studied seven scripts so far, but I make some changes in them, too, as well as make up my own. Even back in Tehran, gray-haired elders in black turbans approached me and marveled at my works: I wrote the name of Allah spiral-shaped, and there has not been such a form of writing before. It was like a kind of a spiritual funnel in which you get caught revolving in a spiral.

– Who can you name as your teacher?

– As I mentioned before, I was lucky to learn many things from the wonderful calligrapher Najip Naqqash. He is also an expert in Islamic studies, translator of old Bulgar literature, an expert in philology, who keenly appreciates the beauty of words. Gulnara Baltanova, a Doctor of Philosophical Sciences and a scholar of Islamic studies also consulted me when I started practicing calligraphy.

Unfortunately, I failed to learn to read or speak Arabic. I use readymade texts in my work. It is difficult for me to learn a language, as I was shell-shocked in the past.

– And who can you name as your pupils?

– Obviously, Roza Khuzina and Gulnaz Ismagilova. They have learned to create very talented original works, I am proud of them. I felt especially happy when I learnt that both of them were chosen, without any support from my part, to participate in the International Exhibition of Calligraphy, receiving a chance to keep their works with the Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy in Moscow.

– What does calligraphy give to the world?

– The Arabic alphabet like no other allows expressing feelings through written characters. I do something that no one else does. Traditionally, tughra comprises several words decorated with floral ornaments. In the beginning I tried following the tradition, but soon realized that I wanted to express a person’s character, their intelligence and individuality through the tughra. To achieve that, you need to give the spectator some hint, which will urge him to unravel the story of the person behind the image.

In my work, I always rely on beauty. I believe it is an integral element of the world. Everyone aspires towards beauty, transforming along the way. And calligraphy creates exactly that: beauty.

– And what are you currently working on?

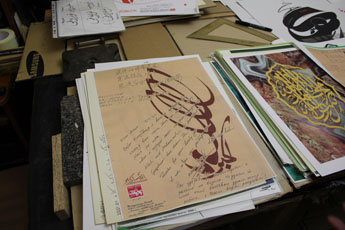

– Tughras, of course! What do you think of these tughras I made for my students? In tughras, I try not only to transfer a person’s name in Arabic letters, but to convey the nature, the interests and the worldview of that person, to show if he or she is phlegmatic or choleric, and so on.

For example, this one is for my apprentice, who works wonders: using the camera, he can portray in one shot half of Kazan, Paris or Naples. He always looks for the highest spot in a city, finds a way to get there and photographs the city’s panoramic view. And if it doesn’t work out he adds the missing details by hand. This looks like his camera with the Eiffel Tower cowering in fear under its lens, but at the same time it is his tughra, containing his first name and surname.

I like to treat every work with a bit of humour.

And this is my future tughra, E Vlademir. I haven't showed it to anyone yet. I will be both Vladimir, as recorded in my passport, and E Vlademir: only one letter changed in the name and the same was added in the beginning. This will serve both as the name, the nom de plume, and the surname. I made these changes because I like to change my image from time to time. And now it’s just the moment for that.

I’ve been experimenting my whole life. Originally my paintings were realistic, I made large scale genre pieces. I rode and walked nearly the whole Baikal-Amur Mainline, immortalizing it in my works. I have plenty of material. I love doing the unusual. For example, there were old works of mine in my workshop. I took them, framed them, and added calligraphy upon them. The result turned out pretty interesting!

So don't be afraid to experiment! Create, write, and grow!

Calligraphy is frozen poetry.