Dwelling in the Fuchun mountains

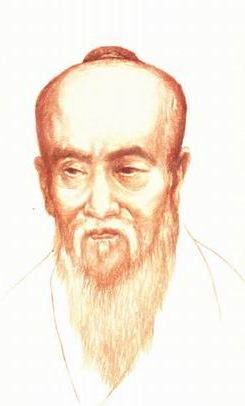

Huang Gongwang

Huang GongwangThe Artist

Huang Gongwang (黄公望), 1269-1354

A native of Changshu, Jiangsu province, Huang came from a poor family and was orphaned at an early age. He was exceptionally gifted as a youth, mastering the Chinese classics at an early age. He studied Taoism and later became a follower of the Quanzhen (全真) Sect. Traveling throughout the Songjiang and Hangzhou regions, he made a living by telling fortunes. Like his interest in calligraphy and music, painting was only something he did on the side. Along with Wu Zhen (吴镇, 1280-1354), Ni Zan (倪瓒,1301-1374), and Wang Meng

(王蒙, 1308-1385), Huang Gongwang is considered one of the Four Great Masters of the Yuan and acknowledged as their leader.

The 'Real' Copy

One copy of Huang's masterpiece was later named the Ziming Scroll (子明卷). Believed to be an excellent copy created in the late Ming Dynasty (1636-1644), this version also bears some 40 poems by the Emperor Qianlong, who penned more than 40,000 poems in his life-time.

In one of Qianlong's poems on the Ziming Scroll, he lavishly praised the painting. Comparing the artist Huang to the greatest poets and calligraphers of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the emperor described the Fuchun Mountains as the epitome of landscape paintings and cherished by the literati.

He described how he verified the painting from examining the inscriptions as well as the brush technique. Qianlong even went as far as to say that the rivers and mountains in the real world were nothing compared to Huang's lively depiction of the marshes, streams, forests, villages, farmers and fishermen in their idealized forms.

Finally, he vowed to return to the painting from time to time as he believed its appreciation would increase his longevity. Emperor Qianlong was 84 when he wrote this poem in 1794. He died in 1799 at the age of 88, after ruling for more than 60 years as one of the longest reigning monarchs in China's history.

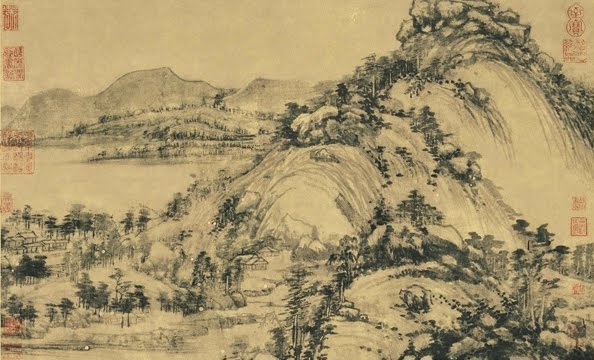

A part of the “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains”

A part of the “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains”The Emperor's Error

Qianlong said that Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains was the pinnacle of Huang Gongwang's works and that he had obtained the original copy with inscriptions by different collectors a year ago, which he believed were faked. The emperor also said that, judging from the "weak strokes of brushes" on this painting, it must be a copy. But he considered that the style of painting was still good enough, so he purchased it with 2000 taels of gold and had it stored in the court.

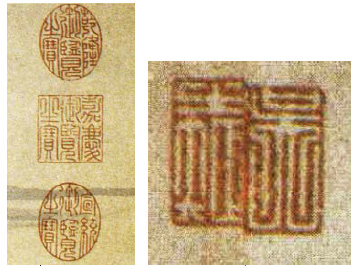

Seals

Emperor Qianlong (reign — 1736-1796)

Emperor Jiaqing (reign — 1796-1820)

Emperor Xuantong (reign — 1908-1912)

Eight pieces of xuan paper were joined for the scroll. There is one seal stamped on top of each joint. The three characters of the link-crossing seal are identified as Wu Zhiju (吴之矩), Wu Zhengzhi (吴正志) father of Wu Hongyu (吴洪裕), the famous Wu who caused the painting to be burnt and separated.

Wu family seals

Wu family sealsIn the early years, traditional Chinese scrolls usually carried inscriptions and the personal seals of the artist, which served to describe the circumstances under which the work was created, as well as to authenticate its originality.

When the painting was passed on to different collectors, other inscriptions or seals would be added, either directly on the scroll or on another piece of paper stuck to the back of the painting. These served as a record of its passage through time.

Later, Chinese ink and brush painting evolved into an art with three indispensable, but complementary elements — poem, calligraphy and painting.

Ink & Brush

This scroll is an idealized panorama of the Fuchun mountains west of Hangzhou, to which Huang had returned in his later years. Beginning with a vast expanse of river scenery from the right, the painting moves on to the mountains and hills, then back to the river and marshes before ending with a conical peak. Finally the landscape fades into the distant ink-washed hills over water. The composition was first laid out in lighter ink and then finished with successive applications of darker and drier brushwork. Sometimes shapes were slightly altered, contours strengthened and textured strokes or groups of trees added. In addition, brush dots were distributed across the work as abstract accents. Buildings, branches and foliage are reduced to minimalist forms as Nature is translated into the artist's own terms of brush and ink.

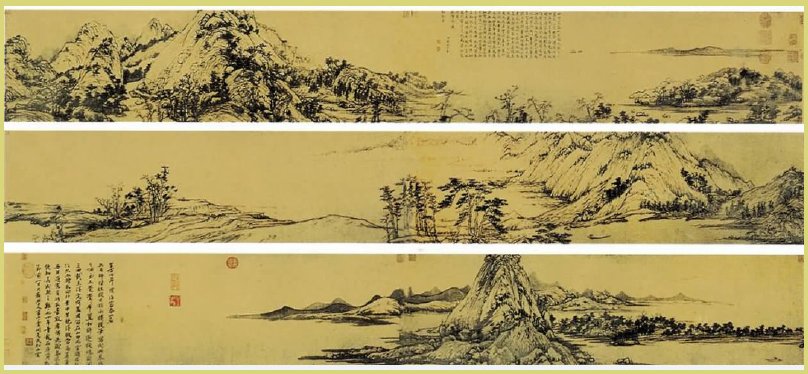

The Remaining Mountain

The smaller segment, measuring slightly more than half a meter, was subsequently named The Remaining Mountain (剩山图). After passing through numerous collectors, it came into the possession of Wu Hufan (吴湖帆), artist and collector, in 1938. Having seen the original copy of the other half — the Master Wuyong's Scroll — he concluded the two were actually part of the same painting. He also recognized the cross-link seal, split into two on the upper left and right of each half. It belonged to Wu Zhiju (吴之矩), the man who passed the painting to his son Wu Hongyu (吴洪裕). After the painting was burnt and damaged, the Wu family placed seals on each link when they reframed the now separated segments. The Remaining Mountain finally found a home in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou.

This is how the picture looks today

This is how the picture looks todaySource: ChinaDaily

Calligraphy is the art of both ideal writing and an ideal soul.