Calligrapher magazine visited Alexander Boyarsky

Alexander Boyarsky, an artist from Saint Petersburg and participant of the 6th International Exhibition of Calligraphy in Moscow, shares the details of his creative path. Boyarsky masters various writing styles and techniques and actively shares his knowledge in an original educational project (The School of Calligraphy).

— Alexander, please tell us how can one learn to understand and love calligraphy?

— I think, anyone is able to understand calligraphy in the “like or dislike” manner. However, entering the world of calligraphy requires the knowledge of some historical scripts, materials, maybe some training to understand your ways with brushes, pointed or broad nibs. Also, there are simpler and more complex scripts. As you dig deeper into the subject, you gradually reach the level where it becomes interesting to start improvising.

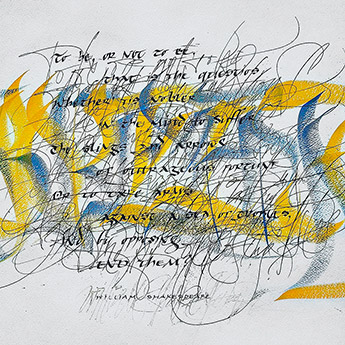

I made a sketch recently, and they asked me if it was italic. I studied it and found that the first letter came from italic but slightly improvised; the second very much resembled a half uncial “A”, “R” came from some English, the next one was from Uncial, and all of them were based on italic. So, overall, it was a combination of scripts, yet it looked balanced, justified from the compositional point of view, and complete.

— Do you track the changes in your own works? What are they about?

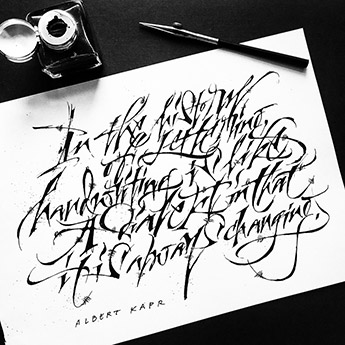

— Sometimes I revise the works produced a few years ago and think of how I would approach this or that sketch now. There are pieces that I still like, but for some of them I would do differently now. The sketches and texts I create these days are technically more profound, the range of scripts keeps expanding, and any new handwriting impacts the rest of the scripts fairly significantly. I spend a lot of time and training looking for new letter forms and some out-of-the-box solutions. It's a potential way. Some people who begin doing calligraphy often follow the “instant creative self-fulfilment” path. I get it, the modern age dictates to get everything overnight, but I believe that the truly fine calligraphy should have a serious foundation.

Today one can find a plenty of examples of amateurish and naive calligraphy or lettering online. It has been said that historical scripts are obsolete and unappealing. However, we see a great number of scripts based on the historical forms, even in computers – or the script this interview is written with.

The basics are never revoked, and to illustrate it I’ll quote a fantastic calligrapher, Villu Toots: he said “An extreme is far from progression, yet it may strike you as one.”

— Do you have any favourite scripts?

— There are the scripts I’m currently using. Say, I can sketch with one script today, and with another one tomorrow. Recently I ran an online training called “Gothic styled italic”, a synthesis of two scripts: italic was born in the 15th century based on Vatican calligraphers’ handwriting, while Fraktur was forming between the 15th and 17th centuries. According to practice, both these scripts complement each other greatly. And today I’m focused on training Spencerian, the American script. I am for the diversity of techniques and scripts, I don’t understand why someone would want to only use pointed nibs and ignore broad nibs, or vice versa.

— Do you think your artworks through or create on impulse?

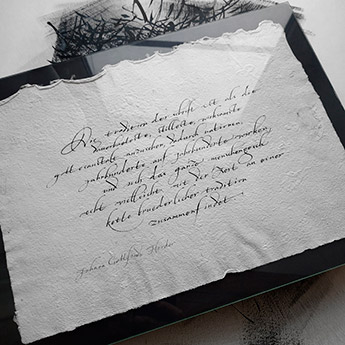

— It depends. Commercial calligraphy, for example, is guided by certain rules: legibility, certain scripts, etc. But there is creative calligraphy that has no such boundaries – you just write the way you feel, depending on what emotions you experience at that particular moment. Sometimes the pieces are thought through to analyse the composition thoroughly and pick the scripts, tools and materials. At times, an artwork can take more than a month. But there are also instances when you can produce a few sketches overnight spontaneously and easily, using the most bold and uncommon solutions.

— Who comes to study calligraphy and why?

— I’ve been teaching for quite some time now, and I often ask people why they do calligraphy. Some say, they do it for their own benefit and pleasure, but more often you see the people who have something to do with designing, wedding calligraphy and lettering, or practicing calligraphers looking to boost their level.

— What are you working on right now, are there any projects?

— There are always some projects, it never happens that you do nothing after having completed another piece. Sometimes you just can’t stop and keep on writing, it’s some sort of a flow where you have to manage to record everything. But some projects are lengthy; you take breaks after every step. Sometimes it happens that there are no shaped ideas at all. But it’s also beneficial: you can practice and copy some unique examples to adopt the experience of the great calligraphers, where every letter curve lets you feel and even see the movement of a professional hand. It yields a great benefit.

Man′s beauty is in the beauty of his writing.