Andrei Drachenkov

Andrei Drachenkov

The town of Vyatka, Russia

Calligrapher, artist, icon-painter, photographer

My journey to calligraphy

Calligraphy for me is the top of a gigantic iceberg called written culture. Having graduated from the Graphic Printing Institute I came back to Vyatka and had no idea what I would be doing there. However I quite soon found myself in the city’s orthodox school. And the turn of the century became a turn in my life. The school had an icon drawing studio on its grounds, which later became the Bukvitsa hand-written book workshop. I planned to teach calligraphy to a group of children there and to study ancient handwriting – my diploma project was dedicated to the first script of the Ostromir Gospel. But the school’s priest gave me another unexpected idea. He said: “In ancient times many people used knot writing. It was a special, symbolic language. Our speech retains some elements reminiscent of that writing. Try to start with this”. And we did start, and got so enthusiastic about it that used this “word weaving” for the entire school year. We managed to find a lot of interesting materials. Personally I discovered for myself the special language of ancient ornaments and got to love mystic medieval handwritten books, where every quirk and whorl has a meaning. Having the knot writing restored (on the level of middle school, of course) we weaved the first quatrain of the school anthem. Next year we scribed the entire anthem with our writings. Working with symbols where every element is a whole notion helped me to transit to abstract depiction of notions and actions. Having studied the principles of Egyptian hieroglyphs we created a small alphabet of glyphs used for writing the anthem. Next we studied antique books, wax tablets, scratching Greek glyphs, birchbark uncial writing. We experienced particular awe and amazement working with the Glagolitic script. We are still working on a very ambitious “face chronicle” project, figuratively calling it our school chronicle, where every script and even the paper we use corresponds to that particular period in history. “In the beginning there was the Word” written in the Glagolitic script – the first line of the Gospel of John – is the first line of our chronicle. Then we write the same text in Greek, Latin and in Slavic block lettering. A fragment of Nestor’s Primary Chronicle was also scribed in uncial. A fragment from the Lives of Saints Cyril and Methodius was written in half-uncial. Next a fragment from The Tale of the Land of Vyatka was put in shorthand. The end result was a cohesive text, where calligraphic peculiarities and writing systems were chronologically tied to the historic sequence of the fragments themselves. Next we worked with plaster and carved the letters of the Greek and Latin alphabets as well as the Church Slavonic letters for the school’s main hall. Working with solid materials helps individuals to comprehend the fundamental rules of sign arrangement in different systems and traditions. Boys especially took a liking to this kind of stone calligraphy while girls preferred working with paper. I myself took interest in a hand-written book at that time. Every work starts with choosing the material: paper, fabric, waxed tablets, birchbark. For each text I want to find the best texture and manner of execution, which would fully reflect its idea. Getting to know medieval books makes us aware of the wisdom and eminence of our ancestors. The handwritten book phenomenon is especially significant in the modern world, where the stream of technological advancement drowns something very important. A century ago in the Vyatka government lived and worked Luka Grebnev – a unique typographer, printer and graphic designer. He revived the culture of the handwritten book, where printing and calligraphic arts were united. This is a unique example of synthesis of many arts. The book as a living organism helps to see the invisible in what we see every day, while calligraphy trains the hand and mind.

Author works

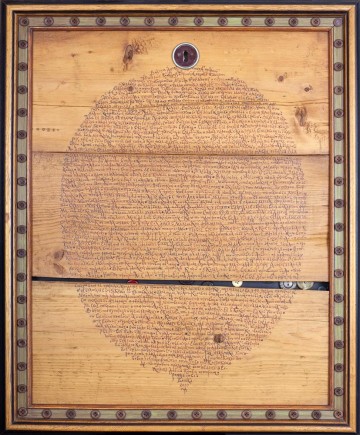

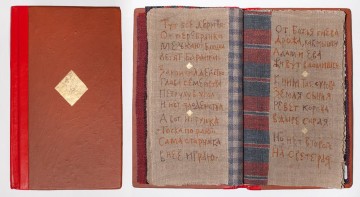

Tale about the green button

Author’s Christmas story about a magical adventure of a button.Written in the manner of Hans Christian Andersen this story brings us the message of prominence of patience, hope, and salvation. Composition illustrates a narrative through real objects and materials. The text in the oval reminds of an old button’s form.

Ink, pen, wood, 60x90 cm, 2011

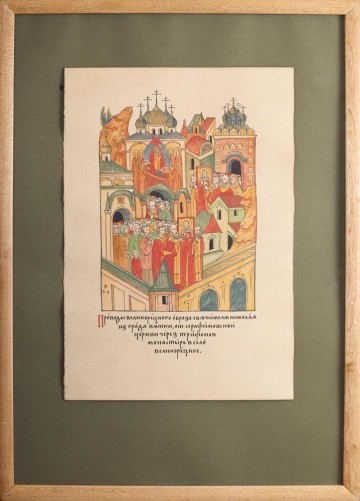

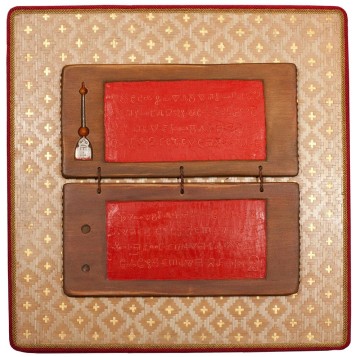

Velikoretsky icon-bearing sacred procession. The left side of the triptych

Paper, ink, brush, pen, 23.5х36 cm, 2008Velikoretsky icon-bearing sacred procession. The central side of the triptych

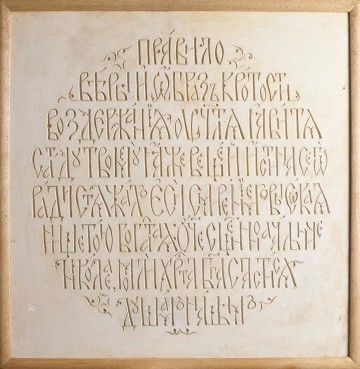

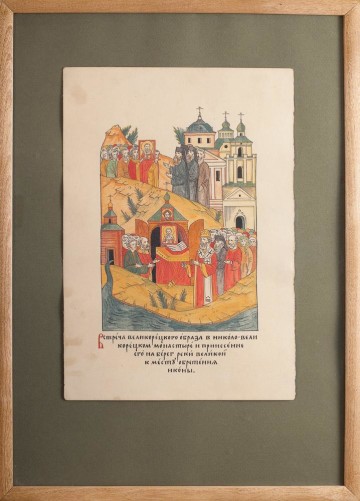

Carving on plaster, 51.5х52 cm, 2008Velikoretsky icon-bearing sacred procession. The right side of the triptych

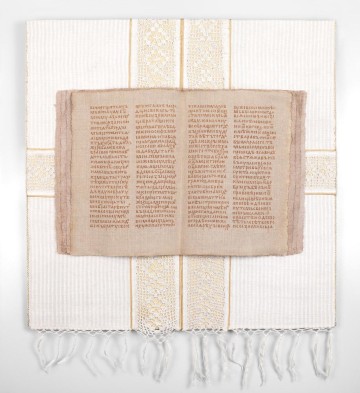

Paper, ink, brush, pen, 23.5х36 cm, 2008The Haze, a poem by Leonid Safronov, a handwritten book

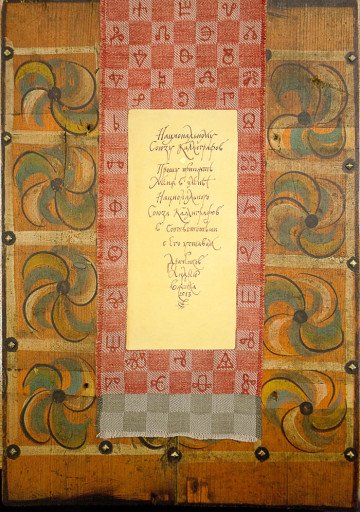

Handmade textile, ink, gold leaf, clay, cardboard, leather, 2011Application to become a member of the National Union of Calligraphers

Wood, textile, paper, ink, 43x30 cm, 201Calligraphy is a remedy and mental gymnastics.