Henry S. R. Kao

Henry S. R. Kao

Hong Kong

Calligrapher, PhD, Professor Emeritus (Psychology) - University of Hong Kong; Professor of Psychology, Sun Yat-Sen University; Guangzhou, China

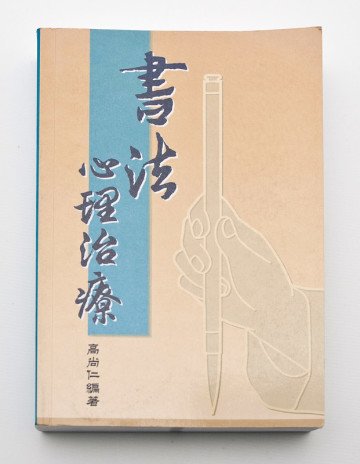

Shufa: Chinese calligraphic handwriting (CCH) for health

This paper presents an overview of psychological research on the Chinese art of calligraphy (Shufa). Using a theoretical framework, we have investigated the scientific nature of calligraphic brush handwriting as well as its treatment effects on behavioural and clinical disorders. The paper begins with an introduction to Chinese calligraphy, Chinese characters, and the character structures. This is followed by an account of a research-based framework of the psychological characteristics of Chinese calligraphy handwriting (CCH). Our basic research includes measures of the writer’s physiological changes associated with the brush-writing act, and the results show that the practitioner experiences relaxation and emotional calmness evident in decelerated respiration, slower heart-rate, decreased blood pressure, and reduced muscular tension. The cognitive effects of the CCH practice included quickened response time and improved performance in discrimination and figure identification, as well as enhanced visual spatial abilities, spatial relations, abstract reasoning, and aspects of memory and attention in the practitioners. Following these findings, our applied and clinical research has resulted in positive effects of the CCH treatment on behavioural changes in individuals with autism, Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); on cognitive improvements in reasoning, judgement, and cognitive facilitation; and on hand steadiness in children with mild retardation; as well as enhanced memory, concentration, spatial orientation, and motor coordination in Alzheimer’s patients. Similarly, we have successfully applied the CCH treatment to patients with psychosomatic diseases of hypertension and diabetes, as well as mental diseases of schizophrenia, depression, and neurosis in terms of the patients’ emotions, concentration, and hospital behaviours. This new system of CCH behavioural treatment has also been applied to users of other writing systems. In summary, the present CCH research has its roots in a Chinese art, has been scientifically investigated, and offers an alternative approach to improved health.

Introduction

Shufa or Chinese calligraphy is the writing of Chinese characters by hand using a soft-tipped brush; it has been used historically as a means of communication. The study of Chinese calligraphy in the past has focused mainly on how to execute

and appreciate it artistically by following the experiences of the great masters. In the last three decades, we have investigated the psychological processes of Chinese brush handwriting from several dimensions of psychology. Chinese characters and the characters’ structuring Chinese brush handwriting involves a process of visual spatial structuring of the elements of the characters. They are written within an imaginary, subdivided square in which the execution of its strokes, the shaping, and the spacing and framing of the character occur. The formation of a character involves inscribing and aligning its strokes according to the patterns of the established character (Billeter, 1990).

The calligraphic writing act involves one’s bodily functions as well as one’s cognitive activities. Motor control and manoeuvring of the brush follow the character configurations. There is, therefore, an integration of the mind, body, and character interwoven in a dynamic graphonomic process (Kao, 2000).

The organization of the character entails certain geometric properties, including the topological principles of connectivity, closure, orientation, and symmetry, etc. In writing, these properties cause the writer’s perceptual, cognitive, and bodily conditions to engage in corresponding adjustments and representations (L. Chen, 1982; Kao, 2000).

Psychological aspects of brush сharacter writing

A research-based general framework has been advanced to highlight the act of brush character writing in any language.

- The writer’s perceptual, cognitive, and motor activities are feedback regulated and are integrated in a dynamic writing task with the writer’s body interfacing the character in an interactive process. The visual-spatial properties of the character affect the cognitive and motor activities of the writer during writing (Kao, 1973, 1976; Kao, Smith, & Knutson, 1969).

- The body–character interlocking involves a projection by the writer of the character configurations in close correspondence and parallel to the body’s changing physical orientations. In this interface, someone’s visual-spatial patterns of the character are varied and more prominently featured than others, and would contribute to the differential complexity of the writing tasks (Kao, Shek, & Lee, 1983).

- The body, as the reference for the writing act, initiates motion according to the geometry of the character and generates the corresponding patterns of the writing movements. Since all scripts share certain geometric properties in their construction, the basic principles of drawing and handwriting for Chinese are common between Chinese and English, e.g., the motor control variability in the writing act. This commonality makes possible the generality of findings from researching Chinese handwriting to alphabetic and other scripts (Kao, l983; Kao & Wong, 1988; Wong & Kao, 1991).

- Because of the softness of the brush tip, the CCH act involves a 3-D motion, which generates a powerful source of impact on the practitioner’s perceptual, cognitive, and physiological changes during its practice. This impact also varies according to the modes of handwriting control, i.e., tracing, copying, and freehand (Shek, Kao, & Chau, l986).

- In character formation, the brush is manoeuvred to produce 2-D strokes, varying in size, form, and direction. The task of the writer is to move the brush to track the established stroke patterns from memory or copybooks. This act resembles a driver’s steering of a car by using its front wheels as cursors in tracking the spatial displacement of the vehicle relative to the road (Kao & Smith, l969). The cursors in CCH tracking take the form of the brush tip.

- A square is the perfect geometric pattern incorporating such features as hole, linearity, symmetry, parallelism, connectivity, and orientation. A Chinese character portrays an imaginary square. With an implied correspondence between the square and the character, a character may vary in terms of its geometric properties. These inherent properties contribute to the differential cognitive effects during character reading and writing (X. F. Chen & Kao, 2002; Kao, 2000; Kao & Chen, 2000).

- Psychophysiological changes associated with CCH writing include heart-rate, respiration, blood pressure, digital pulse volume, EMG, EEG, skin conductance, skin temperature, etc. (Kao, Lam, Robinson, & Yen, 1989).

- Cognitive changes associated with CCH practice include such abilities as clerical speed and accuracy, spatial ability, abstract reasoning, digit span, short-term memory, picture memory, and cognitive reaction time (Kao, 1992a). These changes are varied and affected by the whole motor programme as well as the subprogrammes of the components of the character (Chau, Kao, & Shek, l986).

- Stylistic variations of written characters reflect the individualised forms and organization of the strokes of the character. Chinese characters executed in different calligraphic styles and orthographic forms would lead to variations in the writer’s behavioural responses (Kao, Mak, & Lam, 1986a).

Basic research

A host of experiments measured a writer’s physiological changes associated with the practice of CCH. Common results indicate that subjects experienced relaxation and emotional calmness throughout this writing act. Their respiration rate decelerated, heart-rate slowed down, and blood pressure decreased, and digital pulse volume increased with corresponding reduction in EMG (Kao et al., 1989). The heart-rate can also differentiate different modes of handwriting control (Kao & Shek, l986). Moreover, the practitioner’s EEG activities in the right hemisphere were found to be significantly greater than those in

the left hemisphere during such writing (Kao, Shek, Chau, & Lam, l986b). For the post-task cognitive effects of the CCH,

the subjects performed better in figure identification and form discrimination tasks. A second study showed a significant reaction time reduction in both hemispheres for subjects with calligraphy experience (Gao, 1994). A third study further disclosed that the right hemisphere reaction time reduction was more distinct for experienced calligraphers than the novices (Guo & Kao, l991). Further, a series of experiments has shown that the CCH practice improves abilities in visual attention, spatial ability, perceptual speed and accuracy, spatial relations, abstract reasoning, as well as in response facilitation, short-term memory, and pictorial memory (Kao, 1992b; Kao, Gao, Wang, Cheung, & Chiu, 2000c). In addition, preliminary post-task ERP data disclosed a significant increase of cortical activation in the experimental subjects, but not in the controls (Kao, Gao, Miao, & Liu, 2004).

Applied and clinical research

As for behavioural changes, children with Autism, Attention Deficiency Disorder (ADD), and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) have benefited from the CCH training. The improvements include the ADHD children’s attention and social communication (Kao, Chen, & Chang, l997) as well as the autistic children’s negative behaviour and communication in the family or schools (Kao, Lai, Fok, Gao, & Ma, 2000e). Some CCH cognitive treatments have been conducted. In the case of mild retardation, the treatment resulted in increased visual attention, reasoning, judgement, and cognitive speed and accuracy as well as hand steadiness and control precision (Kao, Hu, & Zhang, 2000d). For the Alzheimer’s patients, the treatment improved their short-term memory, concentration, and temporal and spatial orientation, as well as motor coordination. The normal elderly also improved in their spatial ability and pictorial memory (Kao, 2003; Kao & Gao, 2000; Kao et al., 2000c). For psychosomatic diseases, we started with patients suffering from essential hypertension (Guo, Kao, & Liu, 2001). After the CCH practice, their systolic and diastolic blood pressures showed a significant reduction. A related study reported a reduction of anxiety and an increase of alpha waves, as well as a decrease of heart-rate after the CCH training (Kao, Guo, & Liu, 2001). Further, stress-related conditions of the diabetes II patients and business executives exhibited a post-CCH reduction in states of anxiety and moods (Goan, Ng, & Kao, 2000; Kao, Ding, & Cheng, 2000a).

Finally, we also examined the CCH treatment effects on mental and stroke patients. After a 3-month training schedule, the schizophrenic patients improved significantly in their positive hospital behaviours as well as their negative symptoms, while the control patients made no improvement (Fan, Kao,Wang, & Guo, 1999). In separate study with a 2-week CCH treatment protocol, the stroke patients made significant improvements in their palm strength and fine motor coordination (Chiu, Kao, & Ho, 2002).

Conclusions

This paper has presented an overview of our research on Chinese calligraphic handwriting. These varied findings are founded on a theoretical formulation, on associated basic research, and on varied applications. As for the reasons behind all these positive effects of the practice of CCH, two views are offered. First, the act of brushing causes heightened attention and concentration on the part of practitioners and results in their physiological slowdown and relaxation, causing the subsequent changes in their emotions. Second, concurrent to these states, some cognitive effects occur in relation to a person’s attention and concentration as a function of the geometric characteristics of the writing script, which contribute to the facilitative benefits observed in one’s cognitive activities. We are currently developing our CCH treatment system for broader applications to cover English alphabets and Japanese and Korean scripts, with some success. We are optimistic that this new therapeutic system will be helpful not only to users of the Chinese script, but also to users of other writing systems.

Author works

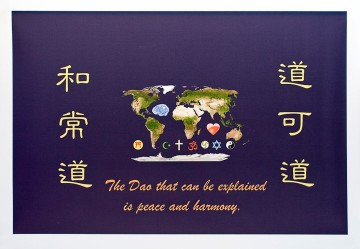

Peace and Harmony in All Faiths

In cooperation with Tin Tin Kao and Xiao Yang Kao (Digital processing). Digital Print on Canvas. Digital processing by Photoshop, 141x101 cm, 2010Modern Calligraphy.

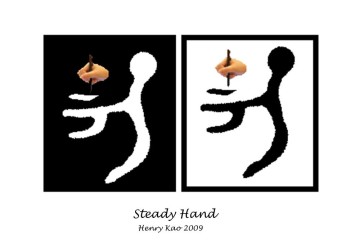

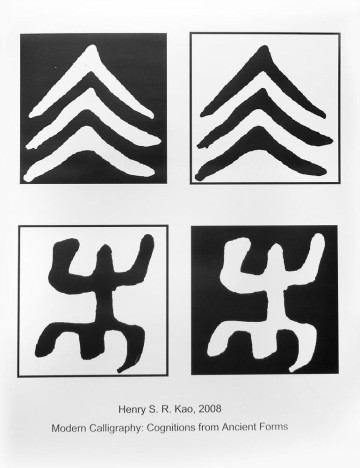

Cognitions from Ancient Forms (poster)

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper; original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 60x84 cm, 2008 Healing Hieroglyphics.

Health in Modern Vases (poster)

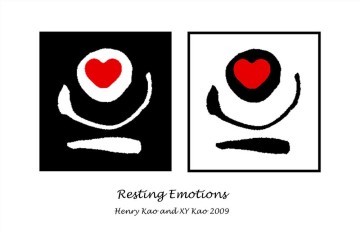

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper; original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 80х64 , 2008 Bilingual Emotions in Contrast

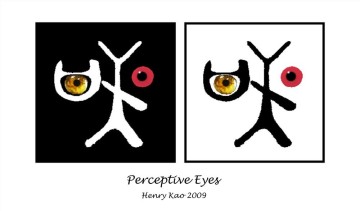

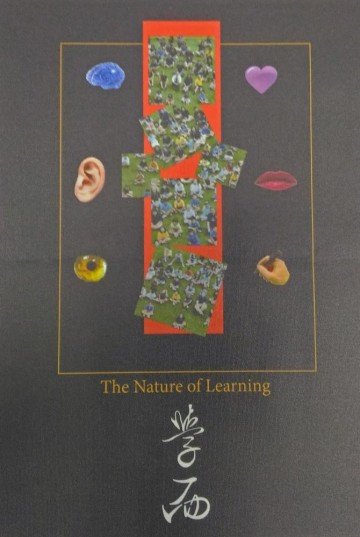

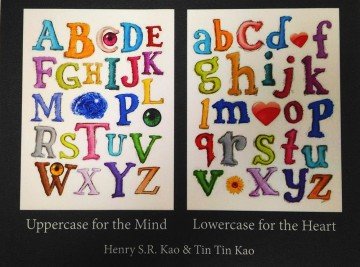

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper; original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 60x84 cm, 2008Bilingual Cognitions in Contrast

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper; original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 60x84 cm, 2008Ancient Minds — Spring

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper; original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 84x60 cm, 2008Ancient Minds — Autumn

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper; original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 84x60 cm, 2008Affect Forms in Ancient China. Image 1

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper, original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 84x60 cm, 2008Affect Forms in Ancient China. Image 2

Photoprint from a computer graphic system, Kodak type photo paper, original characters forming the images in the paintings were first hand drawn on paper and later integrated into the designs through a computer digitization process, 84x60 cm, 2008Calligraphy is the art of both ideal writing and an ideal soul.