Pens that scripted wonders go dry…

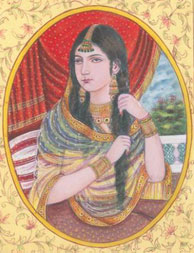

Princess Jodha Bai, 16 century

Princess Jodha Bai, 16 century

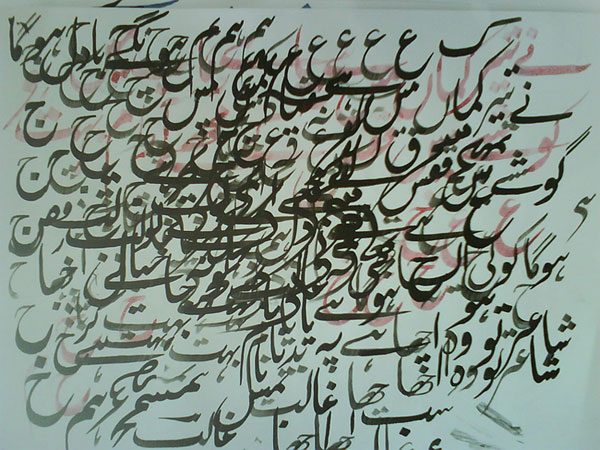

The striking beauty of jewel-like alphabets and designs inscribed on a sheet of paper grabs the immediate attention of the eyes. As Syed Azeem Haider Jafri, wielding two modest tools — a reed pen and ink — begins to write, alphabets transform into gems.

Jafri is the master of calligraphy or Khattati, the Islamic art of fancy handwriting. This unique and decorative style has been admired for centuries for its beauty, and skill and creativity of the artist. Rajput princess Jodha Bai is believed to have mastered it to perfection. But now, this exquisite handwriting style is on the verge of extinction. Reason: it could not withstand the onslaught of modern inventions like computers and printers.

Jafri, who has scripted wonders on papers and stones, leads a non-descript life in the by-lanes of Muftiganj in Old Lucknow. He, in fact, excels as a Tughra artist, considered a notch above calligraphers. Tughra are calligraphic logos or designs depicting the names of the Almighty, the Prophet or the Imams revered by the Muslims. This talented penman knows that calligraphy’s demise is imminent, but that has not diminished his passion for the craft.

The impressions of Jafri’s crafty hands are visible on various imambaras and mosques in the city. Prominent among them being the Zainul Abidin Imambara in Thakurganj, Shahnajaf Imambara and Rauza Hazrat Muslim in Raees Manzil. When goaded, Jafri shares having gifted Tughra to former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf and film stars Farooque Shaikh and Raza Murad among others.

It may take from a week up to three months to complete a single specimen of calligraphy or Tughra. Given the toil and artist’s skills, a single masterpiece is priced between Rs 2000 and Rs 5000. Though these penmen still have many admirers, the number of buyers has plummeted.

Historian Saiyed Anwar Abbas says there are more than 180 styles in calligraphy. «Lucknow, Delhi and Hyderabad were the three prominent centres of calligraphy in India. This style of writing flourished in the Mughal courts and was used in the farmaans, coins and other documents», says Abbas. «In Lucknow, there was a tradition of putting up wasli on the walls of drawing rooms. These were like decorative wall hangings wherein calligraphers would inscribe the couplets and sayings of famous poets and writers», he adds.

«Calligraphy has lost out to economics and technology», moans Agha Mohammed Hasan, one of the last surviving calligraphers in Lucknow. «Till computers came into vogue, several Urdu dailies and magazines used the services of Kitabis (calligraphers). Penmen like us were also sought after to write on the wedding cards. Since computers are time-saving and can produce calligraphy-like designs at much lower rates, the handwriting business drifted away from us», he says. But Hasan quickly adds: «Computers are of no match for the lively and stylish words that flow from the qalam of calligraphers».

Seeing the dwindling fortunes, Hasan brought about an innovation. «From 2001, I started doing calligraphy on stones that are used in houses. This has helped me to preserve the art and also generate some money», says the veteran Kitabi. Hasan continues to move ’kilik’ (calligrapher’s pen) with his frail fingers at his shop, Al-Khattat, in Old Lucknow’s Victoriaganj.

Source: The Times of India

For the largest part ill handwriting in the world is caused by hurry.

(Lewis Carroll)