Brody Neuenschwander

Brody Neuenschwander

Bruges, Belgium

Calligrapher, researcher, art historian

Brief History of Calligraphy in Belgium

As is commonly known, the Low Countries, of which modern Belgium is a part, produced a very large number of illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages. The highpoint of this production was in the 14th and 15th centuries, during which the Book of Hours, a small book of prayers, was produced in ateliers throughout Flanders, Northern France and Italy. Thousands of these richly decorated manuscripts survive in libraries around the world.

The Book of Hours was a product of secular ateliers and intended for a secular public. The general public often thinks these late medieval books were produced by monks for priests, but for the most part this is not true. Books of Hours were prayerbooks for wealthy merchants and members of the elite. It is often said that a manuscript had the value of a small house.

The Low Countries were instrumental in the spread of printing, an event that naturally put a lot of calligraphers out of work. But this very event created a much larger reading public, and this public needed to be taught to read and write. Many calligraphers retrained as printers and teachers of writing in the late 15th and 16th centuries. In the Low Countries, calligraphers developed extravagant styles to attract clients. An excellent example of this is Jan van de Velde, a calligrapher from Antwerp whose scripts are masterpieces of technical control and graphic design. He was active in the late 16th and early 17th century. No calligrapher of his time could match his mastery of the fluid, swirling line and the graphic composition of the page.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, calligraphy in the Low Countries was reduced to the copying of business documents and the production of showy and rather dull moralizing texts. It was only in the mid 20th century that new life appeared in the calligraphy world.

In Belgium, the first modern calligrapher was Jef Boudens, who produced calligraphic texts for print. Born in 1920, his career was interrupted by the Second World War and only took shape after 1945. Very Catholic in his beliefs, he wrote out many pious texts in a rather heavy, often Gothic style. Nevertheless, the graphic strength of his work cannot be underestimated. His work tied Flemish calligraphy into a specifically German history, from which it has slowly emerged in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Jef Boudens′ contribution to calligraphy was, arguably, his five children, all of whom have become lettering artists. Two sons (Pieter Boudens and Kristoffel Boudens) became letter carvers in stone. They have taught countless students the art of lettercarving and have created a wide appreciation of this artform in Flanders. The two daughters of Jef Boudens are calligraphers and have introduced calligraphy to a large public. Jef Boudens also taught a whole generation of new calligraphers in Flanders, and this can be rightly considered the beginning of modern calligraphy in Belgium.

The second major source of interest in calligraphy has been Jan Broes, a resident of Bruges and long time patron of calligraphy. Since the early 1980s, Jan Broes has organized exhibitions of calligraphy in his medieval house every three years. He invites calligraphers and letter carvers from Belgium, Holland, Germany, France and England to exhibit their works. The exhibition is very widely attended and is on an exceptionally high level. It has taught a large public to appreciate very high standards of calligraphy and letter cutting.

In 1993 Brody Neuenschwander moved to Bruges, the home of his wife, Nadine LeBacq. Neuenschwander was trained in England at the Roehampton Institute, a bastion of conservative English calligraphy. He worked for one year as assistant to Donald Jackson, the calligrapher royal, perfecting his traditional skills.

But Neuenschwander arrived in Belgium with a deep disatisfaction of traditional English calligraphy, and used his contact with Jan Broes and Pieter Boudens in Bruges to revolutionize his own work. At the same time (beginning in 1991), Neuenschwander began his long collaboration with film director Peter Greenaway. This allowed him to reconceive calligraphy as a modern artform.

Neuenschwander began teaching calligraphy in Bruges in 1993 and has had a very important influence on most calligraphers in the country ever since. He taught Yves Leterme, who has taken gestural calligraphy to a very high level. Together they founded the Whitespace teaching system, which now has 25 assistant teachers and more than 600 students. The system gives a good classical foundation but aims to bring students to a modern, artistic view of calligraphy in a teaching programme lasting from four to six years.

It would be fair to say that the small city of Bruges, where medieval calligraphy once flourished, now has a greater density of accomplished calligraphers than any other city in Europe. The emphasis in Bruges is on a strong classical foundation and an understanding of calligraphy as a modern artform. The city of Bruges regularly recognizes its many fine calligraphers and supports them with important commissions. The ambition of the city is to be the calligraphic capital of Europe, a goal that it has already achieved.

Author works

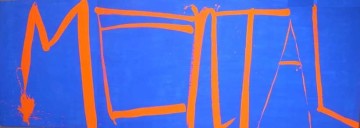

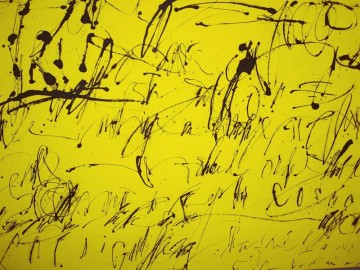

Z — T

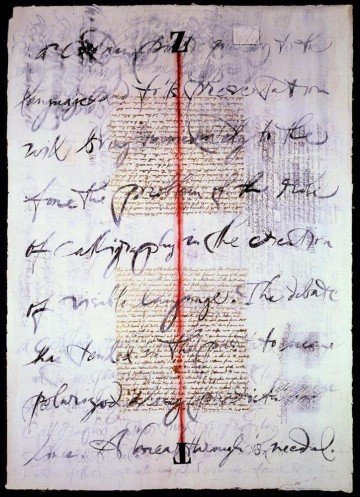

Collage of rice paper on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with whitewash, Chinese ink, gold leaf, red chalk and lead letters, 75x105 cm, 2002Strong people and weak people

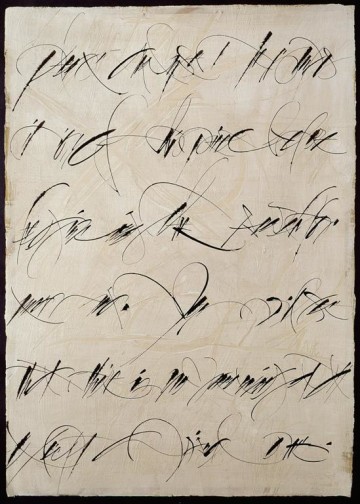

Collage of rice paper on canvas, with whitewash, gouache and Chinese ink, 420 x 100 cm, 2002Please analyse

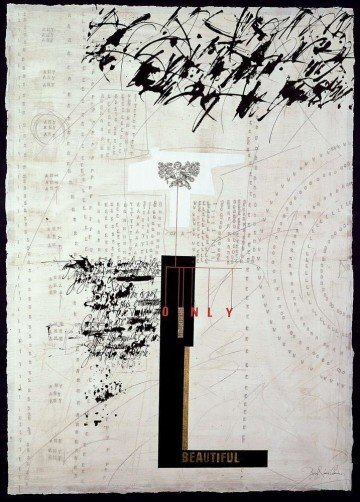

Collage of rice paper on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with whitewash and Chinese ink, 75 x 105 cm, 2000Only beautiful

Collage of rice paper on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with whitewash, Chinese ink, gold leaf and gouache, 75 x 105 cm, 2002Don`t touch me. Sketch

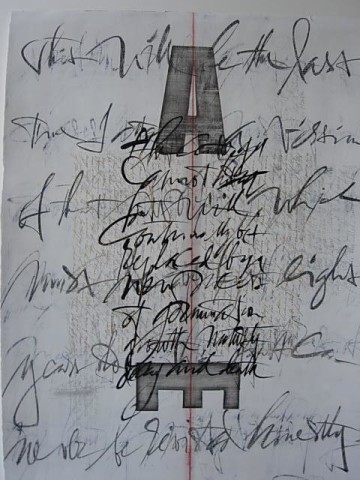

Paper cover sheet with pen trials and other marks made at random by the calligrapher, human form added as a film with microwriting, 210 x 297 mm, 2005Library of Babel

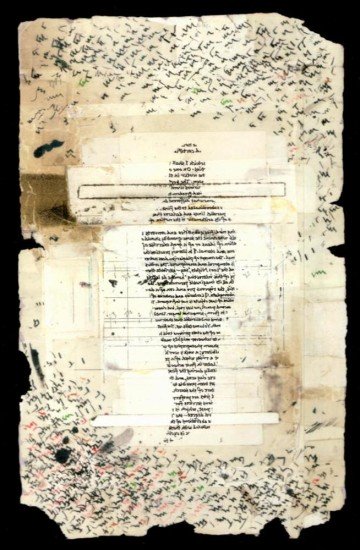

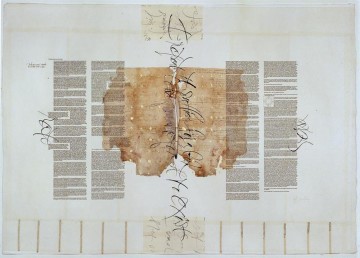

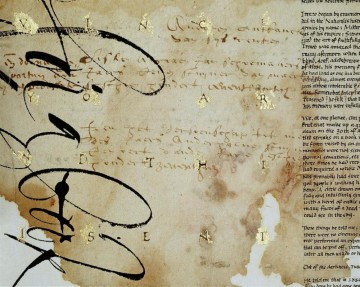

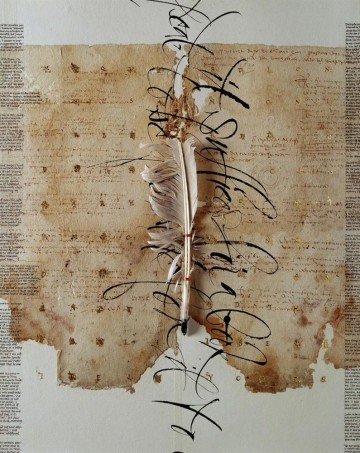

Collage of rice paper and old documents on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with Chinese ink and applied quill pen, 105x75 cm, 2000Library of Babel. Detail 2

Collage of rice paper and old documents on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with Chinese ink and applied quill pen, 105x75 cm, 2000Library of Babel. Detail 1

Collage of rice paper and old documents on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with Chinese ink and applied quill pen, 105x75 cm, 2000Calligraphy is the flower of a man′ s soul.