Tashi Mannox

Tashi Mannox

London, Great Britain

Calligrapher, Thangka painter, BA in Visual Arts (Hons)

The History and traditional uses of the different Tibetan script styles

The Tibetan written language came into existence in the 7th century A.D. under the direction of King Songtsen Gampo. During his reign the enormous task translating the Buddhist Sanskrit texts into Tibetan began. His minister and great scholar Thonmi Sambhota, provided a foundation in the written language and grammar. The different script styles then developed over nine generations, evolving steadily to the 10th century furthering its preservation. By the 19th century, models of Uchen and Umeh script styles were perfected, detailing the exact proportions, which are still in use today.

For Centuries, calligraphy was an important dimension of traditional Tibetan education. Monastic and non-monastic institutions, where the students had to undergo rigorous training in calligraphy for 10 to 15 years, spending at least a couple of years on each style. Listed below are several of the more widely practiced script styles.

The Tibetan written language falls into two main categories:

- Uchen has a ‘header’ line above each letter, as in the Sanskrit Devanagari script, which is why Uchen is often mistaken for Sanskrit. Uchen is the most formal style, and its angular character to the letter's suits well in carving ‘wood blocks’ the traditional method for printing the scriptures.

- Umeh has no ‘header’ and all the other styles are developments of Umeh, such as the next six script style variations listed below.

- Of these, Tsugring or Druchen, or the ‘long style’ is the first to be learned by students who had perfect long strokes on wooden slates. Tsugring is considered a true calligraphy style to be perfected, and an important foundation from which all the other Umeh styles are practiced.

- Tsugtung, or ‘short style’, is practiced next, only after the basic strokes had been thoroughly mastered, and the student had acquired complete discipline over his style, he was then allowed to write on paper; an expensive commodity in Tibet.

- Petsug is mostly used for religious texts as well as epics, stories and special ritual manuscripts. A form of Petsug can also be called Khamyig or Khamdri, which reflects the common use of this script style in the Eastern regions of Tibet: Amdo and Kham. This style is particular for its combination words, where two or three words or a common phrase are abbreviated into one short word.

- Tsugmakhyug has the same shape as Tsugtung, but is smaller and more rounded Stylistically, this style is considered to be between formal calligraphy and Khyug, which is used for ordinary free style handwriting.

- Finally, there are the ornamental styles such as Dru-tsa. The long graceful lines and flamboyant gestures of this style, lends itself well for more artistic free style calligraphy. This is also traditionally used for non-spiritual book titles and important documents.

An important point should be addressed is that of the preservation and practice of the various script styles the Tibetan language offers. The knowledge of understanding Tibetan is a key to a great wealth of wisdom.

As it is a fact that the complete 108 volumes of the Buddha’s teaching ‘Kangur’ and ‘Tengyur’ 224 volume commentaries to both the ‘Sutras’ and ‘Tantras’ are available in Tibetan, where as much of the original Sanskrit volumes have been lost to the dust of time.

Ancient traditions take many generations to develop and mature. However with neglect, such traditions can easily be lost in just one generation.

Documentation and reproduction is essential for their survival.

作者的作品

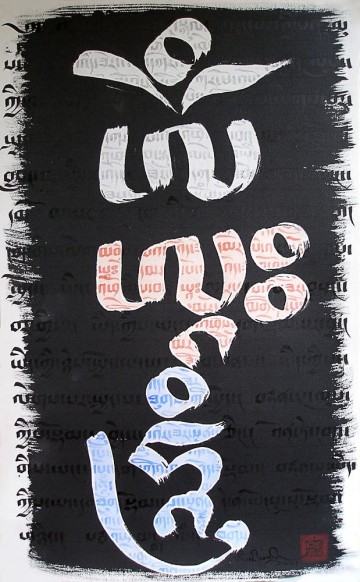

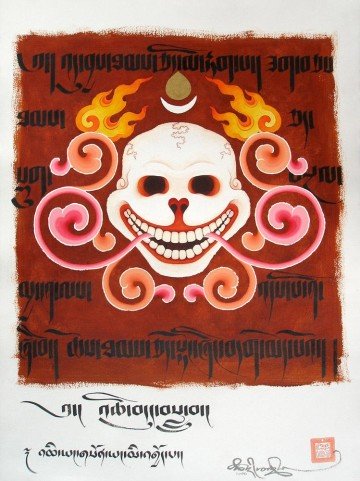

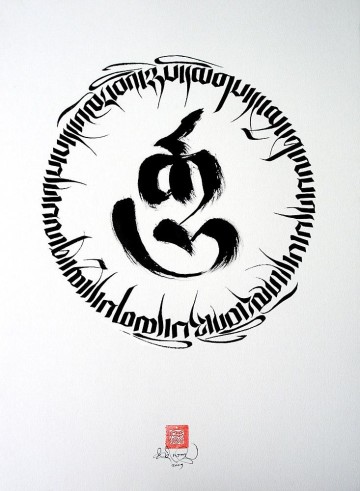

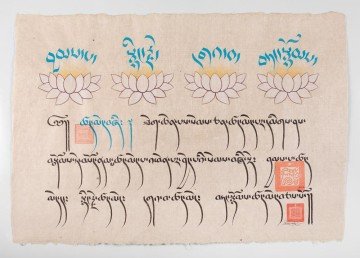

The Emblem of Impermanence

Gold leaf, Acrylic paint and Chinese ink on heavy water-colour paper, 57x76 cm, 2006Merit of Right Action

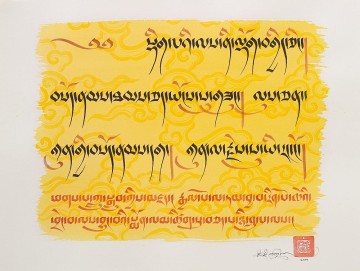

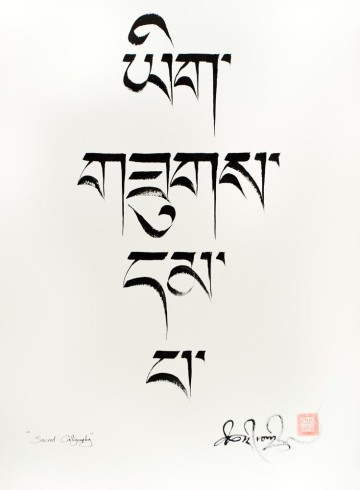

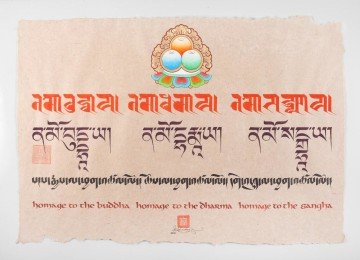

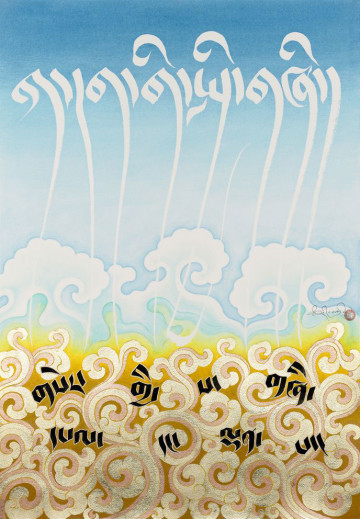

Chinese ink and Japanese mineral paint on a wash of pure saffron, 61x46 cm, 2009.Confident in Faith

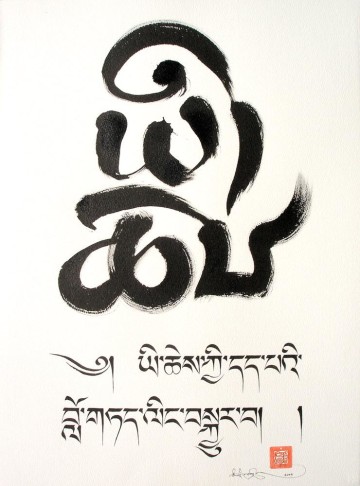

The word, written in Umeh script with a broad-nib pen, translates as "confidence". The carefully crafted Uchen script below translates as "completely trust and surrender in confident faith"Chinese ink on heavy water-colour paper, 57x76 cm, 2009