马卡列米•汉森

马卡列米•汉森

法国 巴黎

书法家、画家、心理分析师

Interview

2009 - Number 5

Calligraphy, the art of making words sing

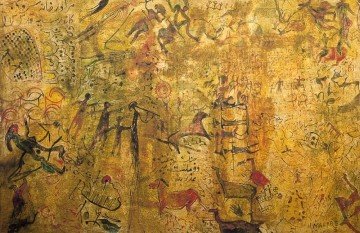

© Hassan Makaremi

© Hassan Makaremi“From rock art to human rights”, painting by Hassan Makaremi.

Persian calligraphy bears the imprint of a range of influences, while Chinese calligraphy remains deeply rooted in local tradition, explains Iranian painter, calligrapher and psychoanalyst, Hassan Makaremi. But, whatever its history, calligraphy embodies our sense of “being in the world”.

At UNESCO’s International Festival of Cultural Diversity in May this year, Hassan Makaremi and the Chinese Grand Master Fan Zeng, gave a presentation entitled, “Dialogue on Calligraphy”. In this interview by Monique Couratier for the UNESCO Courier, he explains how the Persian Nas’taliq style of calligraphy has enabled him to put his ideals into colour and movement, in a personal quest that combines poetic intuition and scientific rigour.

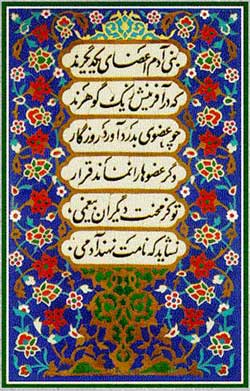

Human beings are members of a whole, In creation of one essence and soul.

If one member is afflicted with pain, other members will also be uneasy.

If you have no sympathy for human pain, the name of human you cannot retain

Poem by the celebrated Persian poet Sa’adi (13th century),

on the pediment of the United Nations headquarters in New York.

What affinities do you share with Master Fan Zeng and how are you different?

What Master Fan Zen and I share, above all, is our relationship to nature. We see the same things, and translate this through calligraphy. Don’t forget that calligraphy is the art of stylizing the written word, which was invented by observing nature. In his inventory of visual forms, Marc Changizi, a researcher at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy in the USA, demonstrated some fifty elements that appear both in nature and in four families of script: cuneiform, hieroglyphics, Chinese and Maya. For both Master Fan Zeng and myself, calligraphy embodies our “being in the world”.

How do we differ? In our relationship to society. Chinese writing, which originated 4000 before the Christian era, remains deeply rooted in nature. There is a direct link between rock art and Chinese characters, which have hardly changed in six thousand years. That is why, across the ages, the line of ink cast by the Chinese calligrapher’s brush continues, instantly, to take the form of a horse, ox or a tiger. It takes the skill of a Master to chant the rhythm of time.

But Persian calligraphy has assimilated a series of outside influences. I am thinking of the Arab-inspired kufi (angular and geometric) and naskh (supple and rounded) scripts, abandoned in the 14th century, as the art moved closer to nature, from which it derived the gentle curves so typical of the nas’taliq style, which inspires my own work. To give you an example, in this script, the egg is symbolized by a voluptuous loop that seems to take flight, light as an eyelash.

This slow progression towards other visions – Mongolian, Arab, Turkish, Indian, etc. – which are reflected in body language and therefore also in the gestures of the calligrapher, means that Persian calligraphy also has a stylized view of [what French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan called] the “speaking being”, this “desiring being” that lives in the metropolis. Chinese calligraphy, on the other hand, remains confined to nature, which it distils or sublimates. Why is this? I am not a specialist of far-eastern philosophy, but I think the explanation may be found in the notion of detachment with respect to desire, as advocated by Buddhism.

© DR

© DR

Poem by Sa’adi, celebrated 13th century Persian poet.

Your encounter with Master Fan Zen is more than simply the sum of your similarities and dissimilarities. Do you have the impression of having established a genuine dialogue?

The very fact that we are present, side-by-side, is a form of dialogue – a dialogue between what is common to both of us, and what separates us. So what is the fruit of this dialogue? No less than life itself! Our commitment to use our brush to trace the curve of the universe is a message, which says that humanity, in all its diversity, is nevertheless one.

If I often use the tree as a metaphor, it is because humanity has common roots, which give it a unity, thousands of branches that provide its diversity (its people, who are both so different and yet so intermixed) and countless leaves, the undulating products of its creative genius. Without its roots, firmly anchored in the ground, without its branches – even if some die while others flourish – without its leaves, continually “started afresh”, the tree could not survive.

And you might say, what about violence? It arises from the fact that certain peoples or individuals think that they exist apart from everything else, outside this common “décor” of our humanity. But, without the sentiment of belonging to the same species and without the recognition of diversity, humanity could not continue to survive. This is the message of our exchange between Chinese and Persian calligraphy. This is also the message of the United Nations, whose New York headquarters has a poem by the illustrious Persian poet, Sa’adi [see box] inscribed over the entrance to its Hall of Nations, and of UNESCO, with which I would be honoured to continue my collaboration to promote “cultural diversity in dialogue”.

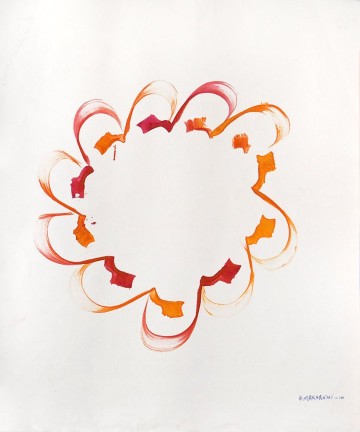

© Hassan Makaremi

© Hassan Makaremi

“Whirling Dervish”, painting by Hassan Makaremi.

Why has calligraphy not flourished in the West? What can it give us today?

In the West, since the 16th century, the choice has been made to opt for rapidity and efficacy, notably by trying to gain mastery over nature. In the East, the preference has been to “tell it” to “write it”, in its fullness and looseness, in its curves and silences, by leaving the space for interpretation, for freedom …

Far from my training as a scientist, there is this idea of renouncing rigour, clarity and concision. But I know that the computer keyboard will never replace the hand. And I reckon that, today, calligraphy represents added value. In a motion that is in harmony with nature, like a whirling Dervish, the gesture of the calligrapher-philosopher-poet turns the words of the Universe into song. That is nas’taliq calligraphy: the alchemy of life!