The Middle East as a Universal Canvas

When it comes to art exhibitions, viewers are used to seeing artwork displayed in galleries, museums and in spaces specifically built for art. But we tend to forget that, every day, we walk in a big, free open-air art gallery: the streets.

In the Middle East — and everywhere else in the world — we witness the most unconventional art on display in the streets. Whether it is a construction site, the colorful vegetables and fruits displayed outside the grocery stores or the young boy going from car to car to sell his roses, all of this is part of an ongoing exhibition.

In Bahrain, street art is mainly a means to proclaim the population’s identity and to honor important figures such as former Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini or Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hasan Nasrallah. «Religious scriptures, aphorisms, and historic references,» writes Saudi-born artist Rana Jarbou, «are written in colorful calligraphy,» in an essay entitled «Bahrain’s Calligraphic Messages.» The Bahraini graffiti illustrating Jarbou’s essay were all created by unknown artists, emphasizing the fact that it is not the name of the creator that matters, but the message. «The truth is in the medium,» continues Jarbou, «and the silenced medium is the message.»

As for Lebanon, it seems that street art is used in more domains than in other countries of the region. Zoghbi’s essay on shop signs, «Calligraphic Shop Signs,» explains that in the 1980s calligraphers were often commissioned «to write the name and description of shops on newly painted white walls.»

We’ve all heard the saying «the clothes don’t make the man,» but it seems to be the opposite for old Lebanese shops since «calligraphy on the wall,» Zoghbi writes, «becomes the identity of the shop.»

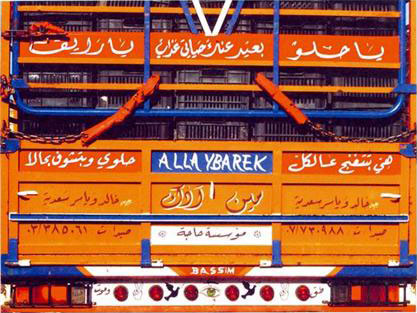

As in the case of shop signs, truck calligraphy is an expression of identity, with the added distinction that much of the script is used as protection against the evil eye. In her essay «Calligraphy on Trucks,» anthropologist and photographer Houda Kassatly describes the practice as a means to «confide to us the amours of the truck driver, his philosophy ... and his ethics.»

Aside from religious sentences such as «the will of God,» much of the calligraphy on trucks are satires of the driver’s status. Calligraphic Arabic advice suggests to women that they should do everything they can not to settle down with a truck driver. «Take these millions but don’t marry a truck driver,» for example, or «Pretty girl: love a poor genius but don’t love a truck driver,» are the types of phrases that can be read on these vehicles.

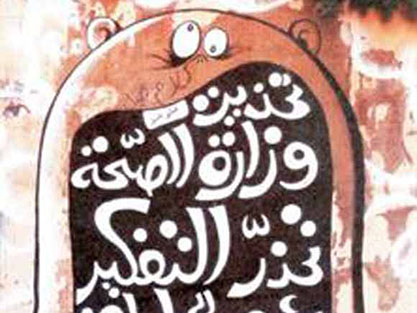

Moving from the highway to the city, Saudi graphic designer Tala Saleh defines Beiruti graffiti as a means to demonstrate one’s ideas and affiliations in a «spray it, don’t say it» culture, in the essay «Marking Beirut.» Whether through political stencils or artistic ones, Lebanese street art quickly developed by the end of the ‘90s with a Western influence.

Famous Lebanese graffiti groups are REK (Red Eye Kamikazes) — composed of seven members — and Hip Hop duo Ashekman. Lebanese graffiti needs «more time to mature in order to achieve a strong Oriental style,» writes Zoghbi, «and to stop copying the West.»

Although Arabic graffiti is considered so commonplace that it is not worth attention, in the Middle East, viewing it is like opening a book on a country’s secrets and multiple identities. This movement, as Don Karl writes, «will continue growing in the years to come.»

Source: The Daily Star Lebanon