Paper Giant

Ancient xuan rice paper is more popular than ever, but its survival is precarious.

Old xuan paper, or Chinese chalk overlay paper, has become a new favorite with collectors. At the first China old xuan paper auction held in Beijing this month, 15,000 sheets of xuan paper (measuring 136 cm by 68 cm) produced by brands such as Red Star and Red Flag fetched a total of 2.66 million Yuan ($425,300; €325,700).

The price of xuan paper has gone up four times since 2009, each time by more than 20 percent. A sheet of old xuan paper made during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) now sells at more than 10,000 Yuan.

Xuan paper origins can be traced back to Jing-Xian county, Anhui province, which was once under the jurisdiction of Xuanzhou prefecture in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), hence its name.

Xuan paper, along with writing brushes, ink sticks, and ink slabs are known as «the Master's Four Treasures»..

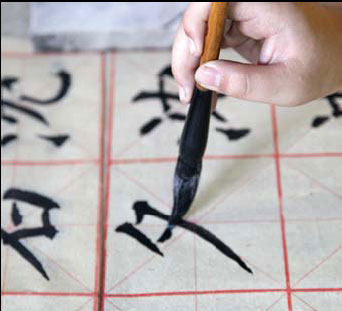

Xuan paper, soft in texture but strong and durable with a high saturation capacity, is the perfect medium for conveying the spirit of Chinese calligraphy and painting.

It has also gained a reputation as «the king of all paper» for it can be stored for a thousand years without its color fading.

A piece of paper more than 5 years old can be considered old xuan paper. The older the paper, the smoother it is to write and paint on.

With the recent influx of money into the xuan paper industry, the top 10 factories around Jingxian county produce an average of 20 billion Yuan worth of paper each year.

But the industry faces two serious obstacles — the lack of younger papermakers, and a limited supply of raw materials.

Xing Chunrong, chief engineer of China Xuan Paper Corporation, says: «The migrant flow of rural youth to urban cities has become the bottleneck for the inheritance of xuan paper making.»

Xing is one of the few in China who are familiar with exactly how xuan paper is made.

«Although the paper enjoys great fame at home and abroad, we have failed to attract enough young people to pursue the old business,» he says.

Having been in the business for 40 years, Xing feels his experience is difficult to pass on. He began his career as a xuan paper worker in 1973 at the factory where descendants of the Cao family — a local family that exclusively held the skills of xuan paper making for centuries — still account for 60 percent of its staff. It was not until the late 1960s that the Caos started to recruit workers from outside the family.

The increasing demand for xuan paper has pushed up China's total production to 1,000 kilotons a year. The bark of the blue sandalwood tree grown in the valleys of Jingxian county is essential for making xuan paper. Although the purchase price of blue sandalwood bark has doubled since 2006, its supply still cannot satisfy expanding production.

Microfibers are abundant in sandalwood bark, which can lead to better damping properties in xuan paper. Mixed with rice straws grown out of the local tidelands that have fewer impurities, these two ingredients can help make the paper appear as white as possible and slow its decay.

Eighteen major procedures and 100 small steps are involved in making the paper, steaming and bleaching being the most important. After the rice straws and the bark are pounded and saturated in spring water for a month, they are cured in limewater at a specific ratio and temperature that are still kept secret.

After curing, the mixture is dried on hill slopes. All these procedures have to be repeated twice before the product is steamed into paper pulp.

During the bleaching that follows, workers have to dip their hands into cold water for long hours, even in winter.

Indoor drying is the next step; workers usually have to spend more than 10 hours in the drying room, which has an average temperature of 40 C.

Xuan paper dates back 1,500 years. It was first recorded in the ancient Chinese books Notes of Past Famous Paintings and New Book of Tang. It was during the late Song Dynasty (960-1279) that the Cao family in Jingxian county monopolized the papermaking business. The practice of collecting xuan paper is similarly ancient, having been around for more than 1,000 years.

A description in a Song Dynasty poem gives us a glimpse of its value: «If you have enough money, buy xuan paper instead of gold, for its smooth surface looks like the clouds in full spring.»

Since the Tang Dynasty, it has been a staple of the literati. There are countless stories and anecdotes that relate xuan paper to big names such as the great painter Ouyang Xun and the Southern Tang Dynasty Emperor Li Yu.

In 1915, xuan paper won a gold award at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, held to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal the previous year.

In 2009, Xing and the art of making xuan paper were included in the National Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

Xing is now devoted to studying xuan paper and introducing new procedures in its manufacture. After studying a large number of historical records, he revived «imperial-only dragon cloud xuan paper» making that had been lost for about 250 years. Unlike traditional xuan paper, the dragon-cloud variety is decorated with dragon patterns.

«Diligence, perceptivity and luck have emboldened me to success,» Xing says. «Unlike other old art, xuan paper is a collective wisdom, and I fear that with speculative production on the rise, how many factories left are still doing it in a devoted manner?»

Xuan paper is the perfect medium for conveying the spirit of Chinese calligraphy

Xuan paper is the perfect medium for conveying the spirit of Chinese calligraphySource: