How a Secret Manuscript Became a Global Bestseller

Nelson Mandela’s biography «The Long Walk to Freedom» became an international bestseller and is being made into a film. But the famous book may never have seen the light of day if it wasn’t for the bravery and persistence of another Robben Island inmate.

Mac Maharaj was one of four long-term prisoners on Robben Island secretly collaborating on the first draft of the autobiography of Nelson Mandela — along with other Africa National Congress activists Ahmed Kathrada and Walter Sisulu.

«Mandela had to write every night. He wrote on average 10-15 pages with very little reference material — he wrote by discussion and recollection,» says the 76-year-old. «The next morning it would circulate to Kathrada and Sisulu for their comments, which would come back to me to transcribe. And the next night he would write another 10-15 pages.»

Their determination to write overcame the fear of being caught.

«We were living in a society where the history of our struggle was not covered anywhere — not even in academia. Everything in history was the history about the white man. So that in itself was an exciting exercise to put down on paper the life of one man who was so central [to the struggle], and whose autobiography was really a political autobiography. One had a sense that Mandela had already become a national and international figure and that it would be an inspiration to read our history.»

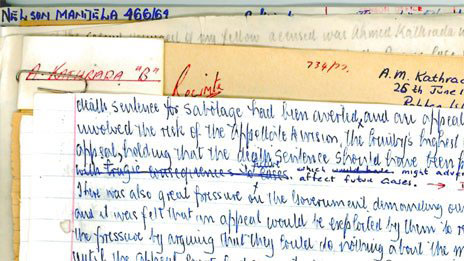

They used thin sheets of lined A4 paper from a stash of stationary available to prisoners, many of whom were studying for degrees — Mr Maharaj added.

Mandela’s writings

Mandela’s writings«I had to transcribe it into a form that I could hide. We used both sides of [the paper], and we used tiny handwriting.»

Mr Maharaj’s painstakingly scribbled transcriptions were hidden amongst his study materials — 60 sheets of paper concealed in the covers of a handmade file that was used to carry statistical maps.

Meanwhile, Mr Mandela’s handwritten copy — the original draft of the book — was put into tin containers and buried in a vegetable patch.

One October afternoon Mac Maharaj was unexpectedly called to the prison offices and told he wouldn’t be returning to his cell. He would be moving on — leaving without his belongings. After a moment of panic, he began arguing with the guards — demanding to return to pack up his books and study materials, which contained the all-important transcriptions. Still apparently oblivious of his clandestine work with Mandela, the guards allowed him to leave with some books, which contained some of the writings. And thinking on his feet, he hatched another plan.

«I had the presence of mind to say, ’My books are lent out, exchanged with people and there are books in my cell that don’t belong to me. So go to Kathrada, go to Sisulu. Ask them to help to pack my books.»

Mr Maharaj was not allowed back to his cell, and was shipped off to Robben Island, but his fellow inmates managed to get the rest of the transcripts out, still undiscovered in his books and his file. Out of prison but under house arrest, he was reunited with his boxes two months later in December 1976.

Soon after he left prison, the guards began to build a wall at the spot in the prison garden where Mandela’s own papers were hidden. The tins were found, and the handwriting on the manuscript was tested — compromising all four men, although only the three still incarcerated could be punished.

After six months of house arrest, Mr Maharaj slipped out of the country and headed for the UK. The secret file had been sent on ahead, to be delivered into the safekeeping of a trusted friend, anti-apartheid activist Rusty Bernstein.

In the summer of 1977, the men met in central London along with another close cohort, Yusef Dadoo. The file was hidden in the Communist Party offices where Rusty worked. After a cup of coffee in a tearoom on nearby Goodge Street, Mr Maharaj finally had the file in his hands.

«I ripped the covers and out came all these pages. Rusty and Dadoo — both their mouths were agape. It was mission accomplished...»

It had to wait another 18 years before being read by millions around the world, because the ANC were firm in their belief that the precious transcript had to wait until after Mr Mandela’s release from jail, to see the light of day. But it formed the framework for his hugely successful autobiography, «Long Walk to Freedom» published in 1995.

Source: BBC News

返回目录