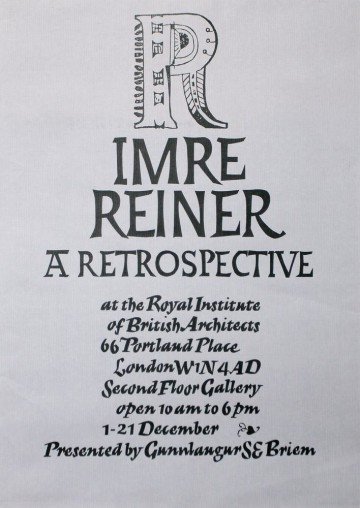

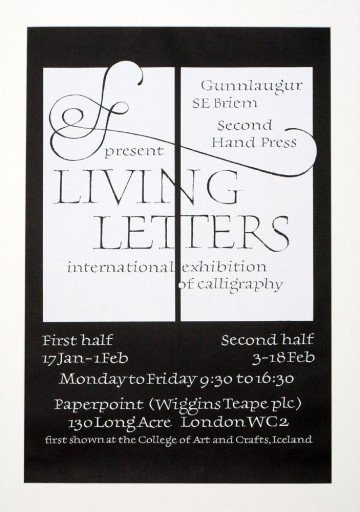

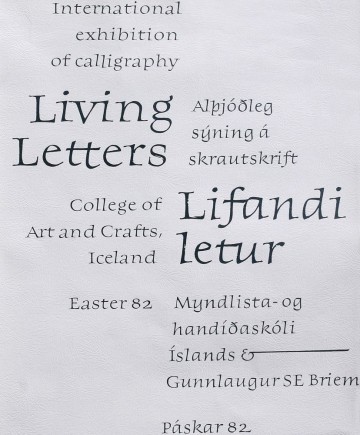

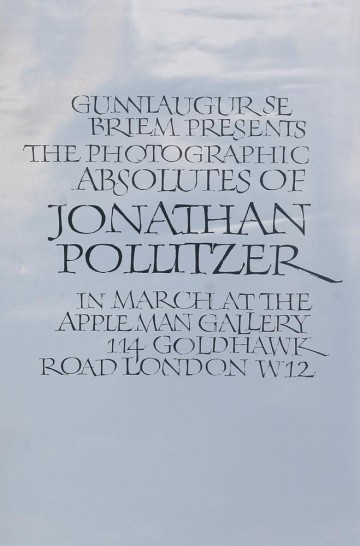

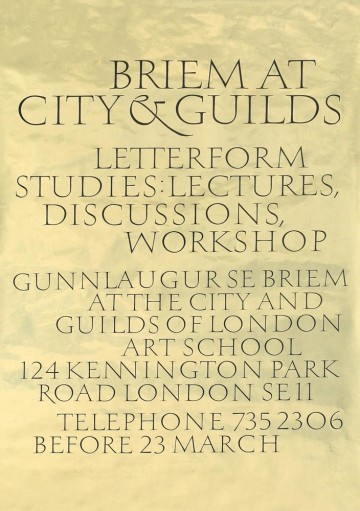

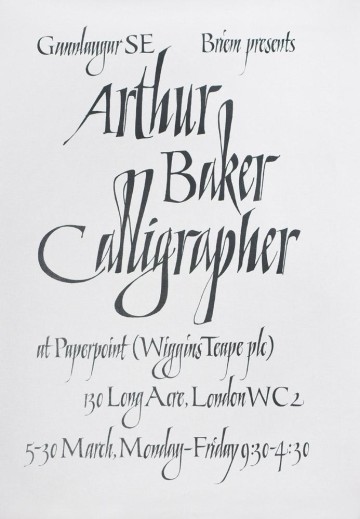

布里姆•贡恩拉乌古尔

布里姆•贡恩拉乌古尔

加利佛尼亚,美国

书法家、设计师、出版人

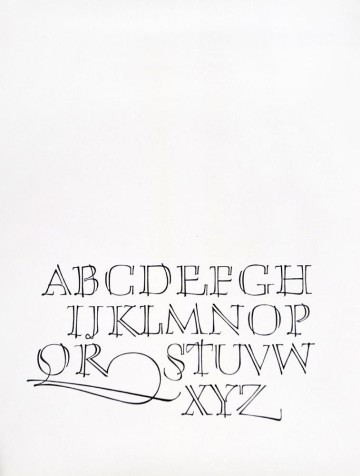

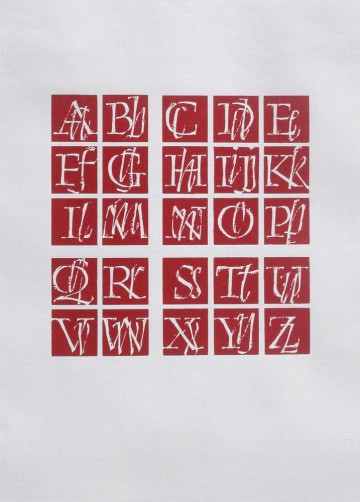

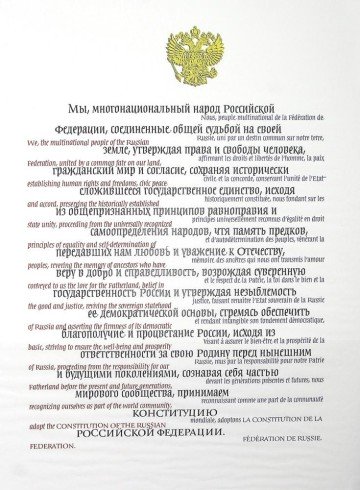

Calligraphy

Let us give thanks to Christopher Sholes, Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In 1867 they laid the foundation for the calligraphy of the Western world. They invented the world′s first commercially successful typewriter.

An army of people made their living in the nineteenth century by writing documents by hand. Machines had been used to produce books for four hundred years. But documents were still made with pens and ink.

The main reason for penmanship classes in schools was to give the students a sellable skill. Clerks were needed to write out correspondence and sales ledgers, legal briefs and government paperwork. A well executed business letter from that time looks at least as attractive as the engravings and oleographs that people hung on their walls. Standards were high and tradition strong. Yet handwriting was not an art form. Twelve hour workdays were commonplace. The pay was low. Still, gifted clerks took pride in their trade and enjoyed the very human desire to show off.

Time passed. In business and government, typewriters replaced pens. But the skills and the aesthetics that surrounded them were not abandoned. People liked beautiful writing and adopted it for their own pleasure. Calligraphy took its place among the decorative arts. It was nurtured by great teachers, such as Edward Johnston in Britain, Rudolf von Larisch in Austria, and Rudolf Koch in Germany. There was a new beginning.

I thank Messrs. Sholes, Glidden and Soule of Milwaukee, who toiled to change their lives with a very useful invention. The teachers I thank for having changed the world, and my life.