Mongolian Calligraphy in Contemporary Art

At the present time Mongolian calligraphy, a very important form of indigenous art, is still relatively rare. More recently however this artwork has become a bit more prevalent as a small number of artists have become increasingly involved in the creation of this work. A comprehensive description of the nature and significance of this art has however yet to be made available to both the Mongolian people at home and interested people abroad as well.

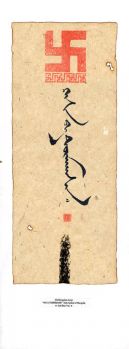

As part of an effort to rectify this situation, Kh. Lkhamsuren, a local art critic, is helping to fill this void as she recently attempted to integrate some historical perspectives on the nature of Mongolia’s art both past and present. She refers to Ts. Dorjpalam’s artwork, and in particular, “ Mongolian Language” “as an important painting that survived Mongolia’s vaunted socialist period. With unadorned but evocative traditional script, featuring the poetry of the eminent poet Byambiin Renchin, this work represents the unique quality and nature of traditional Mongolian culture.

The rich expressive language, written in a highly formalized stoic form, really makes the quality of our Mongolian experience come alive. Like music to the ear our language is the wisdom of our culture”, says Lkhamsuren.

This painting is however important not only for its aesthetic value. It represents an artists’ ability to create work in the face of political opposition, if only tacitly. In judgment of this work, Lkhamsuren says “ this painting is a true example of the resilient spirit of the Mongolian people. It is a very touching work that is symbolic of the natural beauty that exists within our traditional language”.

It is however quite ironic that as this painting has received some attention in recent years it has only now received some critical acclaim. Lkhamsuren says “ it is a work of art that reflects an important period in Mongolian history. We can see that by comparing various historical periods the current social milieu for artists is now relatively open. Certainly this was not the case during the socialist period”.

A brief history of Mongolian art

In a concise description of the extended history of Mongolian art, a framework for understanding Mongolia’s contemporary art scene, Ts. Uranchimeg, an art historian, indicates that the nations’ work can be divided into five distinct periods of time. They include Ancient Art in Mongolia, from the Upper Paleolithic Period (40,000-1200 years ago), the Art of the Steppes Empire (third century B.C to first century A.D.), the Art of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), Buddhist Art of Mongolia, Art of the 19th Century, and Art of the 20th Century.

The Ancient Art of Mongolia, the first period from which we draw this development, is now commonly associated with a bounty of rock drawings that were found throughout the country. Drawings were found carved and painted on rocks, as well as cliffs and mountains. Depictions of animals, hunting scenes and chariots were also prevalent within these carvings and paintings.

These images are however not realistic. Uranchimeg describes them as a meditation of an ancient people. They are quite frankly a series of fascinating images that depict a vision of the world by the earliest people in Mongolian history.

The proceeding period, the Art of the Steppes Empire was created by the Huns or Hsiung Nu. This art was created in the third century B.C., and it lasted until the first century A.D.

In this era animals were often used as subjects in artwork. Felt carpets for example containing animals images were typically fashioned with a superlative quality. The artwork often contained expressive movements of fighting beasts, reflecting considerable knowledge of both the nature and behavior of these creatures.

The succeeding empires of the Sianbi (Shien-pi) and Jujan (Jujuan) in comparison left no traces of art at all. But each succeeding state had a script of its own. These scripts were routinely carved upon wooden blocks.

The Sianbi were master craftsmen in both leather and wood. The Jujuan were accomplished artisans with iron, leather, ceramic and wood. Of considerable interest is the fact that the Sianbi had an orchestra with 80 instruments and their own national hymn, which was played at the start and end of epic battles. Both groups of people constructed temples for worship as well.

By the middle of the sixth century the Turkic Empire was firmly established as its people defeated the Jujuan. The emperor was for the first time given the title Khaan and the empire was named Khaganate. The steppe nomad Turks were the first to create a phonetic script within this region, and a large number of monuments were created at this time as well. Among the most noted monuments were statues of the “stone men”. The “stone men” represent Turkic warriors usually standing in a long robe, holding a cup filled with fire, the other hand gripping the handle of a knife.

In addition to the “stone men”, important burial sites of Turkic leaders can be found in several areas of Mongolia. These include statues with Turkic writing, of buried people, and of animals. The burial sites were organized as whole complexes with buildings, temples and numerous sculptures.

In 740 however the Turks were defeated and succeeded by the Uighurs. The Uighurs a semi-nomadic people, who in addition to their cattle breeding activities had highly prosperous agricultural and trade businesses, most notably, lucrative trading markets along the legendary Silk Road.

Uighur cities were important cultural centers too. They contained temples and palaces ornamented with elaborately painted frescoes on subjects that ranged from everyday life to Buddhist themes. Uighur mural paintings have been preserved, and along with sculpture, and arts and crafts, they are known as the masterpieces of Central Asian art.

It is interesting to note that the Uighurs had an alphabet-based script that was subsequently adopted by Mongolians during the Mongol Empire. It is the traditional Mongolian script that is still used today. And as a tribute to these developments, there are still memorial monuments with Uighur writing, representative of the highly developed culture of this period.

But like the preceding empires, the Uighur Empire also fell, in this particular case to the Khitans in 840. The Khitans were also a semi-nomadic people. They produced two types of scripts. One bore no resemblance to any other script in Asia, the other shared similarities to Chinese writing.

The Khitans created a range of art including literature, architecture, music and dance. Landscapes, portraits and genre paintings were created within their predominant era of influence. Poetry and travel diaries also existed. And districts of commerce, craftsmanship and travelers were also established.

To their demise however, between 1115-1118 the Jurjens, a vassal tribe rebelled, occupying 50 Khitan towns. In 1118, the entire Khitan Empire collapsed from the attacks of the Jurjens.

But in 1206, as fate would have it, a man named Temuujin united all of the Mongolian tribes. He was subsequently pronounced Chinngis Khaan, the Great Khaan of Mongolia. This led to a military conquest that resulted in the largest Empire in human history. The Mongolian people then played an important role in facilitating the exchange of ideas in arts and culture, between both Asia and Europe.

As part of his reign and lasting influence, Chinngis Khaan chose Kharhorum as the capital city of the great Mongol Empire. Built by his son and successor, Ugudei, the city was located by four gates. The eastern gate was adjacent to a market in cereals and corn, the western gate, sheep and goats, the southern gate, bulls and carts, and the northern gate, near horses.

In Kharhorum, the renowned capital city, the Khan resided in a grand palace called “Tumen Amgalan” or “ten thousand times tranquility”. It was built of bricks and had three main doors with sixty-four columns. Thousands of people could sometimes be seen in the palace, situated in a city that contained Buddhist temples, mosques and a church. But perhaps the most significant surviving artwork of this period is the portraits of Mongolian Khaans and their wives. Made in the thirteenth century these portraits illustrate the impact of Khitan painting, and are purportedly the creation of Kara Khosun, a Mongolian artist who worked in the court.

In comparison, the art of the Middle Ages was purely Buddhist. Buddhism was introduced to Mongolia several times via the Silk Road, with the Uighurs and during the Mongol Empire as well. It was however only in the sixteenth century that Altaan Khaan converted to Lamaism. Shortly thereafter it was adopted as the national religion of Mongolia as Altan Khaan, granted the title Dalai Lama to Sodnomjamtso, the most eminent monk of Tibet.

In 1586 the first Lamaist monastery was built on the remains of Kharhorum. This trend continued until the twentieth century as numerous monasteries were built throughout the country. These temples were built in Chinese and Tibetan styles along with a model based on the traditional Mongolian ger and tent.

The medieval period was also the time of Mongolia’s most prominent artist, Zanabazar. Born in 1635, a descendant of Chinngis Khan, at the age of 5 he was given the religious title Unduur Gegeen. And at the age of 14 he studied in Tibet, where the Dalai Lama recognized him as a first Khutuktu, or reincarnation of Bogd Jebzundamba. Upon returning to Mongolia he began building temples and monasteries, only to become the first Khutuktu of Mongolia, called Bogd Gegeen.

Among his considerable talents Zanabazar was known for his sculpture. Zanabazar’s works reveal his deep knowledge about the iconic proportions of a human body in both Tibetan and Indian philosophy. His statues amaze viewers with their perfect proportion and symmetry. A beautiful oval face, a straight nose, a small slightly open mouth, and eyes in deep meditation, became the classical features of a deity in Buddhist sculpture.

In the 19th century much of the development in Mongolian art was based in Urga, a main city in Mongolia. Much like Kharhorum, Urga, now known as Ulaanbaatar, became the meeting place for artists and craftsmen of the highest quality. Within this period, tangka paintings were the most pervasive style of art, created with different techniques such as nagtan, martan and gartan.

As all artists and educated people were monks during this period of time, Tangka paintings were considered a means of expressing one’s spirituality within a traditional Buddhist framework. To start a tangka, the artist awoke at dawn, cleansed his body, and by reading the prayers of a particular deity, purified his soul. The artist then made the first brushstrokes at the hour of good luck and fortune.

By the dawn of the 20th century however, Mongolia’s Buddhist artwork was becoming increasingly secular. Familiarity with European portraits, and internal changes within the Buddhist community began to have far reaching affects. All of this was apparent in the artwork of B. Sharav, a monk, who became one of the era’s most influential artists.

Nicknamed Marzan, which literally means funny, he began to dabble in a variety of styles that were clearly outside the proscribed areas of convention. Sharav became associated with genre painting, the emergence of European style portraits, graphic art, and posters. Some of his work even served as visual propaganda for the communist revolution.

By the 1940’s, approximately two decades after the establishment of the People’s Republic of Mongolia, Soviet style socialist realism became the dominant style of art. Art depicting the lives of herders and workers, reflecting socialist values became the preferred style of art. The lines were clearly drawn. And any attempts to challenge the boundaries with other interpretive descriptions could elicit harsh rebukes from select individuals in official circles.

But by the late 1960’s the fawning embers of discontent began to burn with more than just a little intensity. On July 20th, 1968, “The First Exhibition of Young Painters” opened in the Exhibition Hall of the Union of Mongolian Artists. The Mongolian government immediately shut down the exhibition, labeling the artwork “the art of capitalists”. Both the participants and the Chairman of the UMA suffered strict punishments from the Communist Party as a result of this artwork.

Politics and painting

In reference to the socialist period, Ch. Jamyangsuren, a specialist on Mongolian language and culture at the Mongolian National University seemed a bit reluctant to comment on the impact of Marxist ideology on Mongolian art. Jamyangsuren did however emphasize that although Mongolian script had been listed as the official writing of the Mongolian people during the founding of the constitution of the Peoples Republic of Mongolia, it was only two short decades thereafter, that Russian based Cyrillic became dominant. With this in mind, it is hard to believe that Mongolians like Jamyansuren, who share a significant pride in their nations language and culture, would not be more than a little dismayed at the affects of recent history.

And while Jamyangsuren may have chosen not to point the finger at specific individuals who affected the nations politics, and culture, he was quite willing to discuss some of the purported consequences of a flawed educational policy that has continued to have a lasting impact until this day. In a critique of the current state of education, Jamyangsuren says “many Mogolian people between 40-60 years of age seem to have some disdain for the nation’s traditional script. This may stem from their own personal insecurities, as relatively few of these people are adept in using this writing. This undoubtedly causes embarrassment, as they must maintain a degree of superiority over their students to maintain their fragile egos”.

“Among Mongolia’s young students however there has been some progress. The nation’s traditional script has now become a part of contemporary classrooms. But this modest revival, as pleasing as it may be, still falls far short of what it should be”.

In a critique of the nations policy on language and culture, Jamyangsuren says “ few students are receiving the type of rigorous training that would allow students to develop an in depth understanding of their language and culture. The traditional script, language, and literature are surely the best teacher”.

“Sadly at the onset of our democratic movement several parliament members made pledges to advance the use of traditional script, only to retract their promises at a later point in time. And many members of the local community now argue that because of international trends, and the impact of globalization, learning traditional script has become impractical. But clearly efforts should be made to preserve our traditional culture and make the necessary adaptations to allow our writing to flourish during the 21st century”.

On the merit of an ancient art form

When Jamyangsuren speaks of Mongolian calligraphy his love of the art form really becomes quite apparent. In a moment of self-revelation Jamyansuren said, “ I am really just a slave to the brush. I consider it an artistic endeavor for the scientific development of spiritual culture”.

“As it is an abstract art of line and space, it allows the artist to develop new creative images from within a traditional format. And from a personal perspective I can say that it provides the opportunity for the Mongolian artist to overcome the devastating effects of poverty. It creates feelings of nostalgia. It reaffirms the basic Mongolian identity. And it conjures images of our ancestors. Perhaps there is no other art form that has such a dramatic affect upon the human spirit and soul”.

“Some of my teachers have called Mongolian calligraphy an art in paradise. It is a mental process that produces great happiness and a profound depth of consciousness. You become so absorbed in the entire creative process your spirit becomes released. It is the ultimate freedom”.

“Mongolian calligraphy promotes language development, philosophical thought and critical thinking. It has also been known to reduce stress, promote feelings of wellness and provide deep relaxation. In my opinion it is the basic essence of our nomadic civilization.”

A new Mongolian calligraphy

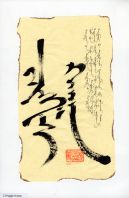

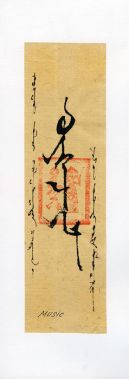

Arguably one of the most gifted contemporary artists to create paintings with Mongolian calligraphy is D. Battumur. Two of Battumur’s most recent paintings, Mountain and Ovoo are examples of a new style of Mongolian calligraphy. Both are fresh illustrations of the innate spirituality that thrives in aspects of traditional Mongolian culture.

In “Mountain” thick protruding characters that appear to be pregnant with meaning are cast amidst a white background. Battumur has referred to the whiteness as snow in the sky. The image of the mountain cast amidst both the snow and sky was created to produce feelings of harmony between heaven and earth.

In “Ovoo”, Battumur once again forms a spiritual communion with nature. As the ovoo is a mound of stones constructed atop a mountain, it is believed that by adding stones to this convex shaped hillock, good fortune will come and physical ailments fade. Battumur has undoubtedly chosen the ovoo as a topic for his art as it is not only a symbol for luck. It is a lasting representation of ancient traditions that exist within Mongolia to this day.

Traditional images

When we consider traditional images in Mongolian calligraphy it is difficult to not to connect this art form with a range of issues related to the modernization of Mongolia. Mongolian calligraphy is by its very nature an ancient form of art. As a result artists who create calligraphy will inevitably convey messages about the relationship between this traditional art form and the changes that are occurring within the greater society. The affects of modernization are undoubtedly a recurring theme.

If we consider the artwork of Battumur for example, we find that the images in his work are deeply rooted in an ancient Mongolian psychology. Yet they have emerged from within a contemporary social context. This contrast provides the art with a depth that may often be a missing element in other forms of artwork at the present time.

In a simple yet eloquent description of the source of this depth, that belies his informal friendly down to earth style, Battumur has indicated that the inspiration for his work is derived from both the natural elements and his family. He indicated that it is essential that his ink be mixed with water taken from a pure river stream. And it is also important that the work be created in resonance with the rising sun.

As he pondered upon the impact of significant others upon his art, Battumur cites the importance of his grandmother. He said that as he was first introduced to Mongolian script as a high school student, it was his grandmother who inculcated a sense of discipline to allow him to master this language. He also cites the significance of Vladislav Smirnov, an influential art teacher at the Stroganov Institute in Moscow where he was a student of graphic arts.

Venerating the past

It is reasonable to conclude that Battumur represents a new generation in Mongolian artwork. As an artist he is youthful and exuberant, yet at the same time, mature. He combines images of the past with a fresh new vision that is unrestrained, creative and thoughtful.

In a recent painting simply called “I”, Battumur makes a bold dynamic statement about the assertion of the self. Battumur is not an artist to be bound by tradition. He has simply developed a new means to forge his own creative niche in the Mongolian art world by reinterpreting the traditions of the past.

“Battumur says when I create my art I feel I am in control of my own destiny. At the same time I am deeply involved in our cultural traditions. It is the greatest feeling.”

“As I progress as an artist I hope to continue to find new ways to express myself. I just want to give proper respect and honour to my ancestors, as other Mongolian artists would do. Mongolian calligraphy is such an important art form. I just think of it as a vital, vivid depiction of my mother tongue. Nothing could be more important, could it?”

返回目录