King Kowloon's “Wordaland”

Another message of the King

Another message of the KingSome people think that Tsang Tsou-choi is mad. The self-proclaimed King Kowloon used the city of Hong Kong as his royal parchment to send messages to his people.

Some saw his ‘street calligraphy’ as a nuisance, and the law certainly thought so: the King was prosecuted more than once. But you can’t call the King a vandal. Vandals’ works are faceless and weightless; but the King’s indelible calligraphy exists in many Hongkongers’ collective memory. His works have graced magazine covers, appeared on Be@rbrick toys and Vespas, and have even been sold at auctions (one for almost $500,000). Exhibitions were curated in his name and books were written to chronicle his life.

Tsang’s work needs little introduction. He used Chinese ink to paint on any available wall and surface in the city, turning it into his own «wordaland». The unique typography attracted international attention. Artists, designers and illustrators duly paid pilgrimage to the King from all over the world. French street artist Invader tells exactly why Tsang’s work is so special: «Most of the graffiti you see around the world are made with Western alphabets. It was very interesting for me to see something different. For a start, it was extremely different from New York’s graffiti style».

There are different theories on how Tsang Tsou-choi began writing in the street. The most plausible theory, according to Tsang’s son, is that in 1956, the 35-year-old Tsang was involved in a serious traffic accident near the Three Mountains King’s Temple [三山國王廟] in Choi Hung. After he came out of his coma, his temperament changed completely. Tsang began scrawling on the street, recalling facts he had once read at his ancestral hall back in Liantang Village, China, where Tsang was originally from and where his wedding took place. He had read that his great-grandfather was Tsang Gwong-jing, a prime minister in Zhou dynasty who was a major landowner in Hong Kong.

Tsang mostly wrote about three subject matters: history, ancestry and family. Believing he was a messenger for Tai Gong and related to the Imperial family, he would curse the Queen of England for seizing his land (Kowloon) without his consent. Historical events would be mentioned but were most likely quoted incorrectly or incoherently. Tsang also calligraphied facts about his ancestors, naming individuals from his family tree. His own family was also one of his subjects. He would mention his wife and his children’s names and their addresses.

This April, Hong Kong will see the largest Tsang Tsou-choi exhibition created, curated by Joel Chung and co-presented by Swire Island East and Hong Kong Creates. Chung is a long term associate of Tsang who brought him ink and food and also edited three books about the eccentric artist.

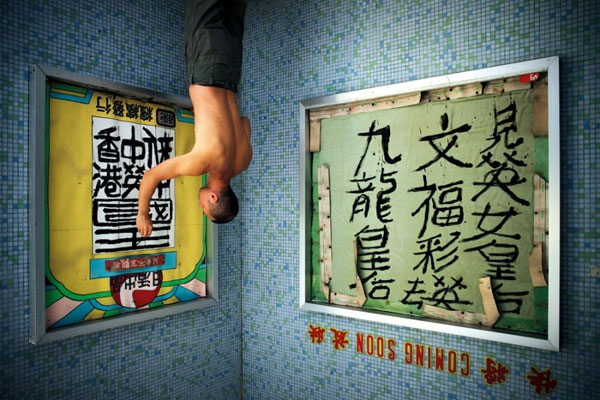

The six-zone exhibition, ‘Memories of King Kowloon’, features over 300 calligraphy inscriptions by Tsang, including works on paper and on various objects. There are also some «royal possessions» on display. There is a zone where artists made tribute work to commemorate the King. Thomas Lin’s tribute video, Tête-Bêche, was filmed with an inverted video camera (an inverted Joel Chung acts as a reincarnation of Tsang and calligraphies the right way round in public places.) The message is that society might often be wrong, but one’s value should always be right.

«As a kid I always saw Tsang drawing in the street, but I never thought about approaching him, let alone question why [he was doing this],» says Thomas Lin who had posted the video.

«A year after he died in 2007, I began studying the culture of Hong Kong and chose Tsang as my topic. I think Tsang has left a huge question mark for us: how come nobody really valued his work when he was alive? And after he died, the government wasted no time to erase his work — which was by then renowned internationally. Tsang initiated a much needed debate about art in Hong Kong: does public art affect our lives? It’s about time we all start thinking».

Source: Time Out