Calligraphy is 'more than beautiful handwriting'

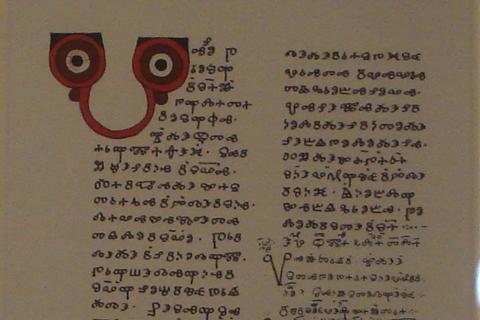

In the middle of the IXth century, when Cyril and Methodius brought Christianity from Greece to the Slavs, they left behind a paper trail of old texts and new alphabets. Glagolitic alphabet still has “uncertain origin” and so the brothers are better known and better credited for Cyrillic, an alphabet that is still in official use today in countries like Serbia, Bulgaria, and Russia. The two writing systems, the oldest known Slavic scripts, came about by necessity: Cyril and Methodius needed to get the Bible translated and transcribed in a way future generations would be able to read.

Some 1,150 years later, Goce Durtanoski displayed faithful reproductions of the manuscripts at the Emauzy monastery, hoping to bring the old Slavic calligraphic heritage to a generation that now reads so much more, generally in digital form though and almost always in Latin script. For the 42-year-old Durtanoski, tradition is important.

“We bring the past to the present,” Durtanoski says over a cup of coffee at a café in Bochum, Germany, a city almost completely rebuilt since the allies struck at the Ruhrgebiet, the Nazis' industrial heart, in World War II. “This is especially important in Europe.”

Durtanoski maintains cultural, family and business ties — he enjoys reasonable success with calligraphy as the Prague exhibit shows, but he also does something like 100 other things — especially in his native Macedonia, which preserves its Orthodox and Cyrillic traditions well. He goes by “George”, his Macedonian Christian name anglicized, but he'll translate or transliterate that, too, depending on the audience. And it's a large and growing audience: Bochum, with a population of some 500,000-odd inhabitants, is a German city big enough to forgive a Macedonian who grew up in the Netherlands and currently has an art show running in the Czech Republic for not knowing everybody. Durtanoski, however, seems to be kissing the waitress hello, waving across the street to passers-by and flagging down the owner of an Italian restaurant (and switching to a pidgin of German and Spanish, which he speaks fluently, having studied in Barcelona) to sit for a glass of wine.

All that to become nearer to people, which is part of what draws Durtanoski to calligraphy and the sacred texts in an outdated alphabet he had displayed at the monastery.

“As a kid, I was always interested in archaeology, and we went many times to visit archaeological sites in Macedonia, which is very rich with them,” Durtanoski says. “We always had so many questions about what was there. I think this calligraphy I do now has its roots from my childhood.” It is as if Durtanoski is digging into Europe's past with every pen stroke, rediscovering the commonalities that allow him to move so fluently through this multilingual, multicultural, multitextual reality. “Calligraphy is more than beautiful handwriting,” Durtanoski says of his old-fashioned scripts currently displayed in Emauzy monastery.

If you miss the show at Emauzy, don't fret: As Cyril and Methodius took their work through Great Moravia in the 860s, Durtanoski, too, will take the show east in their anniversary year, displaying the scripts wherever they might once have been read, wherever they might now be forgotten.

Durtanoski's work faithfully reproduces Glagolitic texts dating back more than 1000 years

Durtanoski's work faithfully reproduces Glagolitic texts dating back more than 1000 yearsand makes them accessible to a digital generation.

Source: The Prague Post